Now an archaeological site in Iran, the ancient city of Parseh known as Persepolis is a relic of Persian Achaemenid Empire from 2500 years ago. Now called Persepolis, the city was founded by Darius the Great in 518 BC as the ceremonial capital of the empire. Considering the greatness of the Achaemenid Empire in ancient Iran, which covered a significant part of the eastern part of the world, we can understand the glory of the headquarters of these kings in Persepolis.

On an immense half-artificial, half-natural terrace, the great king created an impressive palace complex inspired by Mesopotamian models. The importance and quality of the ruins at Persepolis led to its recognition by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site since 1979.

History of Persepolis

Though evidence of some prehistoric settlement at the site has been unearthed, Persepolis inscriptions reveal that construction of Parseh began under Darius I (r.522–486 BC). As a new king, Darius made Persepolis the new capital of Persia that could replace Pasargadae, the capital and burial place of Cyrus the Great. Built in a remote and mountainous region, Persepolis could not be used as royal residence and was mainly visited in the spring in occasion of Iranian new year celebration called Nowruz.

Many parts of this complex were built and decorated during the reign of Darius I, Xerxes and Artaxerxes I; but the construction and completion of Persepolis palaces continued until the end of the Achaemenid rule. The luxurious palaces of Persepolis were used as the spring residence of Achaemenid kings for centuries and are still considered as one of the most prominent and enduring historical sites of ancient Iran.

Alexander Mosaic, showing Battle of Issus, from the House of the Faun, Pompeii

Alexander Mosaic, showing Battle of Issus, from the House of the Faun, Pompeii

The glory days of Persepolis continued until Alexander the Great invaded Iran in around 330 BC. Alexander’s troops looted the treasury of Persepolis, plundered the city and burned the palace of Xerxes; probably to symbolize the end of his Panhellenic war of revenge. But the fire spread to other places and destroyed large parts of Persepolis. Reportedly, In 316 BC Persepolis was still the capital of Persia and an important province of the Macedonian empire, but the city gradually declined in the Seleucid period and after on. Today, relatively well-preserved ruins attest to Persepolis’ ancient glory.

Function of Persepolis

The exact function of Persepolis still remains enigmatic. It was obviously not one of the largest cities in Persian Empire but appears to have been a grand ceremonial complex that was only occupied seasonally. Recently most archaeologists agreed on the idea that it was especially used for celebrating Nowruz, the Persian New Year held at the spring equinox. It is still an important annual festivity in modern Iran. The Iranian nobility and the tributary parts of the empire came to Persepolis to offer their gifts to the king, as represented in the stairway reliefs.

How to go to Persepolis?

Persepolis is located in a pleasant climate area northeast of Shiraz, near Marvdasht town in Fars province. Despite the tropical nature of many parts of Fars province, this region near Marvdasht has a cool and temperate climate due to its mountainous environment. Persepolis is located in mountainous areas between the villages of Firoozi, Kanareh and Estkhr.

The distance from Shiraz to Persepolis is about 60 km. To go to Persepolis, If you enter Fars province from the north, you do not need to go to Shiraz. After passing Sa’adat Shahr you will reach Marvdasht highway and after passing the villages of Hashtijan and Istakhr, you will reach the entrance road of Persepolis. Everything is signposted in English so there is no need to worry!

To get to this point from Shiraz, we have to travel 60 km away from the city by a private car or taxi. From Shiraz to Marvdasht, there are also minibuses at Karandish Bus Terminal .

Ruins of Tachara palace, Persepolis, Iran

Ruins of Tachara palace, Persepolis, Iran

How much time do I need for Persepolis visit?

Persepolis and Naqsh-e Rostam are usually visited together on the same day. Rather than driving all the way to Pasargadae and back you can better use your time focusing on Persepolis and Naqsh. Persepolis is a massive site that you can easily spend a full day in. For a guided tour of Persepolis and neighboring sites you would need 5-6 hours.

The necropolis at Naqsh-e Rostam is small and one hour should be more than enough.

Guide to visit Persepolis

Locally called Takht-e Jamshid (meaning the Throne of King Jamshid), Persepolis was one of the ancient capitals of Persia that was founded by Darius I in the late 6th century BC. Its ruins lie 60 km north-east of the city of Shiraz, in an industrial town called Marvdasht, where the dry climate has helped to preserve much of the Persepolis architectural wonders.

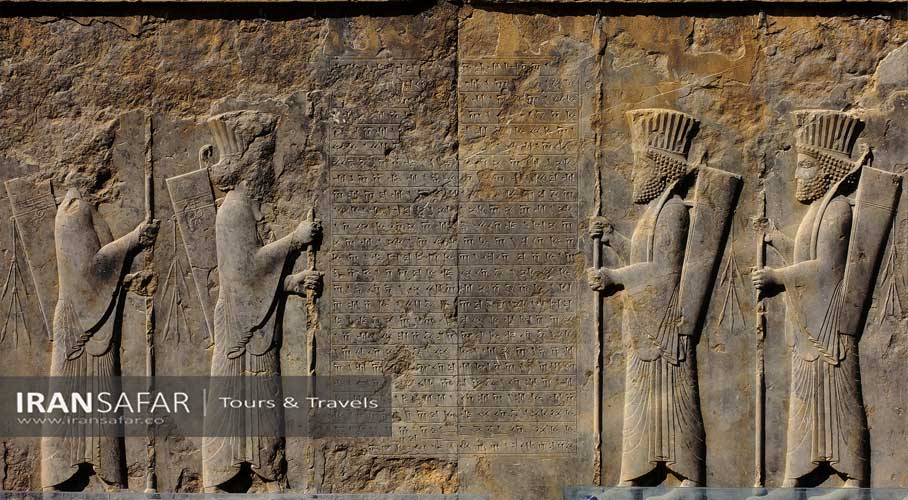

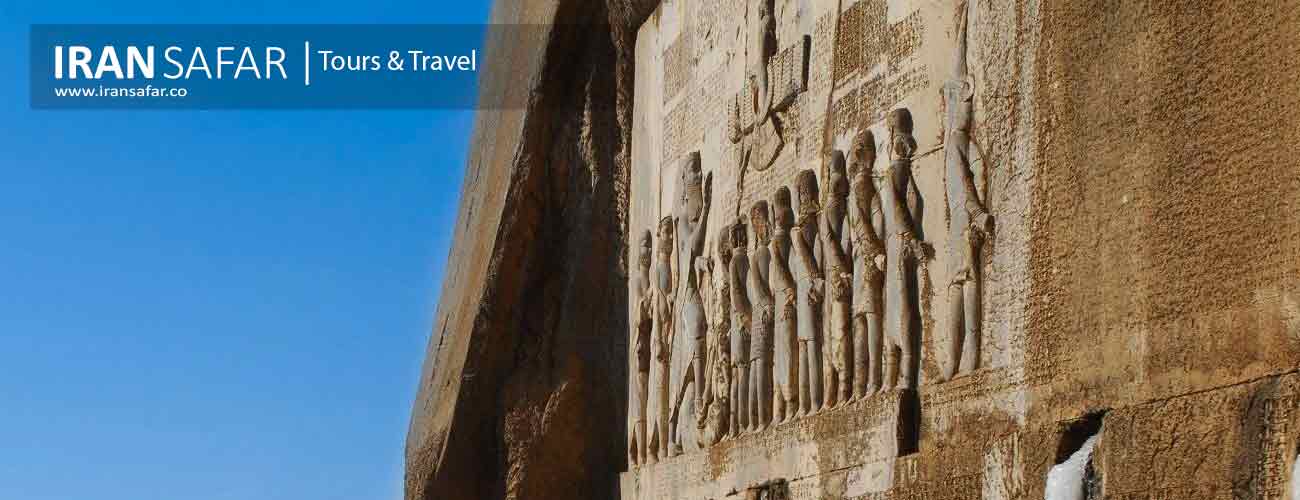

Among the most important artifacts discovered in Persepolis site, are inscriptions and bas-reliefs that have been inscribed in cuneiform and put in the walls of palaces and buildings. Due to the antiquity of Persepolis, these findings are of the most important evidences of early civilizations and archaeologists from around the world are working to decode, translate and read these inscriptions. Many parts of the lines engraved on the inscriptions are understood today; But decipherment of these inscriptions is still going on in different parts of the world.

By carefully examining the sculptures, reliefs, capitals, inscriptions and other excavations in Persepolis and according to the objects found in the area, experts have been able to figure out that the Achaemenids had little experience of stone architecture. But they were able to import craftsmen from all over the empire to develop a hybrid imperial style influenced from Mesopotamia, Egypt and Lydia in Anatolia, as well as Greece. The style was probably first developed in Apadana (the Palace of Darius I in Susa), but the most numerous and complete survivals are at Persepolis.

In total, there are more than 3,000 reliefs in different parts of Persepolis palaces, in all of which common concepts can be found. The number of these carvings is not comparable to other parts of Persia, and it can be concluded that masonry during the Achaemenid period began in Persepolis. The first scientific excavations at Persepolis were carried out by Ernst Herzfeld and Erich Schmidt representing the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. They conducted excavations for eight seasons, beginning in 1930, and included other nearby sites. Most of the inscriptions discovered in Persepolis have been read by the same American team and the results have been published.

Persepolis Architecture

The typical feature of Persian architecture was its broad-ranging nature with elements derived from Assyrian, Egyptian, Median and Greek cultures -of course, this is due to the size of the Persian Empire – all merged together but producing a unique Persian identity seen in the finished project such as Persepolis. Achaemenid architecture is academically classified under Persian architecture in terms of its style and design.

Undoubtedly, Achaemenid period was a period of artistic growth that left an remarkable architectural legacy ranging from Cyrus the Great’s modest tomb in Pasargadae to the splendid structures of the sumptuous palaces of Persepolis; Perhaps the most striking extant structures to date.

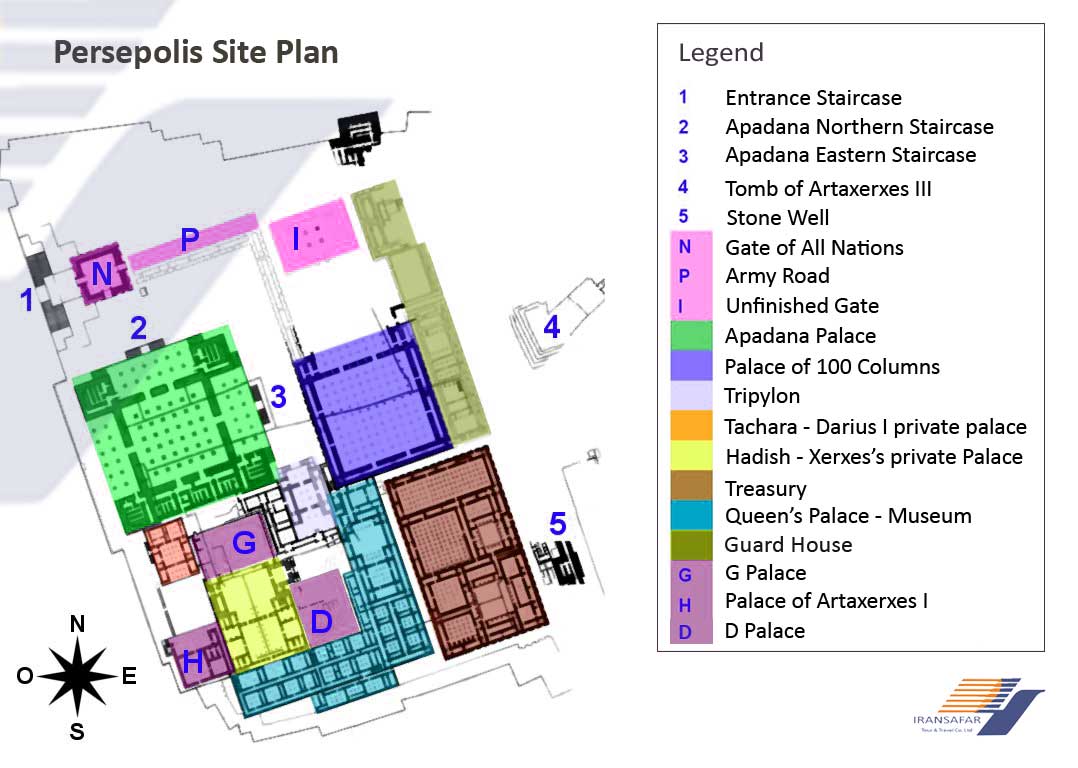

Persepolis Site Plan & Map

Plan of Persepolis Terrace – Map of the site

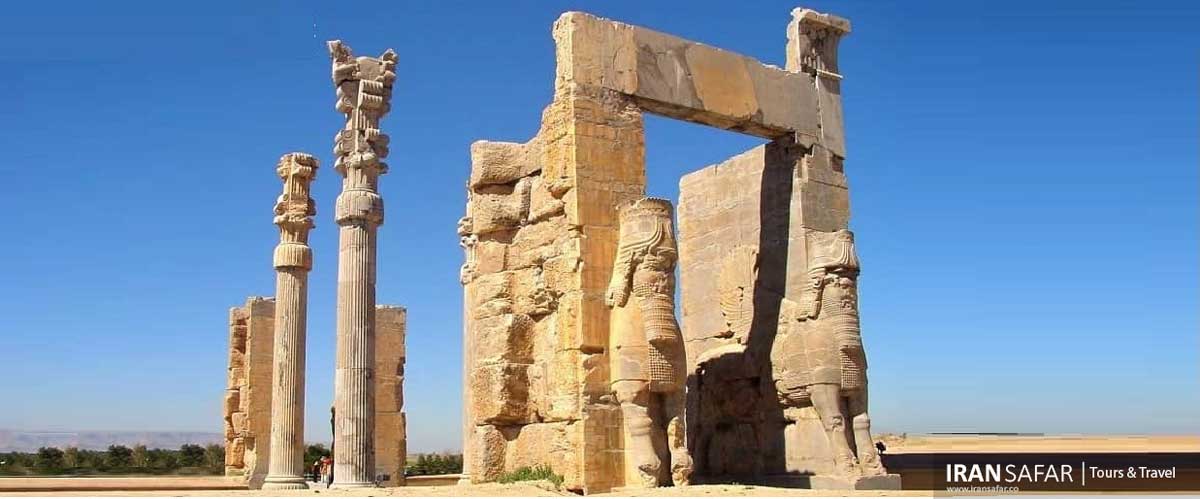

Gate of All Nations

The Gate of All Nations (Old Persian: duvarthim visadahyum) also known as the Gate of Xerxes is located right on top of the entrance staircase of the ancient city of Persepolis. According to its trilingual inscription it was constructed by the order of King Xerxes (r.486-465 BC),

The gate structure consisted of one massive hall whose roof was supported by four stone pillars. All around this room ran a stone bench designed for delegations waiting to be summoned before the king. The outside walls, made of adobe bricks, were decorated with multiple niches. Each of the three walls, on the east, west, and south, had very large stone doorways.

On the main entrance (western side of the building) a pair of gigantic stone bulls welcomed the guests and on the opposite side, two Assyrian style Lamassus stood at the eastern doorway. Engraved above each of the four colossi is a trilingual cuneiform inscription attesting to Xerxes having built and fulfilled the gate:

Xerxes’ Inscription on Gate of Nations

The great god is Ahuramazda, who created this earth, who created heaven, who created man, who created happiness for man, who made Xerxes king, a king of many, a Lord of many. I (am) Xerxes, the great king, the king of kings, the king of all countries and many men, the king in this great earth far and wide, the son of Darius, the Achaemenid. King Xerxes says: by the favor of Ahuramazda this Gate of All Nations I built. Much else that is beautiful was built in Pârsâ, which I built and my father built. Whatever has been built and seems beautiful – all that we built by the favor of Ahuramazda. May Ahuramazda preserve me, my kingdom, what has been built by me, and what has been built by my father. That, indeed, may Ahuramazda preserve.

Lamssu from Nimrud, Iraq, (9th century BC – British Museum) vs Persian Lamassu (6th century BC – Persepolis)

Lamssu from Nimrud, Iraq, (9th century BC – British Museum) vs Persian Lamassu (6th century BC – Persepolis)

Apadana palace and the Eastern Stairway

Apadana Palace, also known as Audience Palace, was used mainly for great receptions by the kings. It was one of the most beautiful and magnificent buildings in Persepolis, built during the reign of Darius I and his successor Xerxes. Construction of the palace began in 515 BC and took thirty years to complete and according to a discovered inscription it was originally called the Columned Palace. But due to similarities between this palace and Darius’ Apadana palace in Susa, archaeologists named it after its Susan prototype.

The main hall is rectangular and has 36 columns and three porches in the north, east and west. Each porch also had 12 columns. Of all the 72 pillars of the Apadana Palace, Thirteen still stand on the enormous platform and another one has been rebuilt end erected. On the four sides of the Apadana Hall were four guard towers. The beauties of Apadana Hall would have been indescribable in the past and a study on this place shows that countless artists have participated in it’s construction. With a capacity of more than 10,000 people, the hall was supported by columns with two-headed bull capitals. By the brick walls of the palace, water channels were dug for the time of rain.

Apadana Architecture

This palace is clearly different from many similar structures in terms of architecture. The surface of this building, which has an area of about 3660 square meters, is built three meters above the courtyard. A large hall with 36 columns is located in the center. To the east, west and north of this hall, three porches with 12 columns have been built. There are four towers in the outer four corners of the hall, and in the south of the central hall, there is a set of guard rooms. To enter the palace, there are two stairs on either side of the north porch and the east porch. The central hall can fit in more than 10,000 audience. The high and wide ceiling of the hall has been raised on 6 rows of 6 columns with a height of about 20 meters. Walls with a width of 3.25 meters are made of raw clay bricks and were painted in green-gray color- with a layer of plaster.

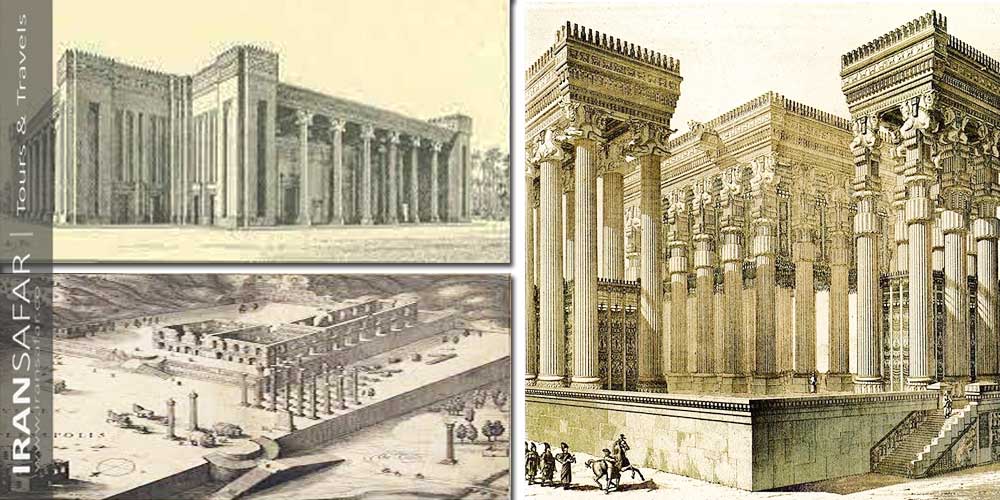

Apadana reconstruction image

Apadana reconstruction image

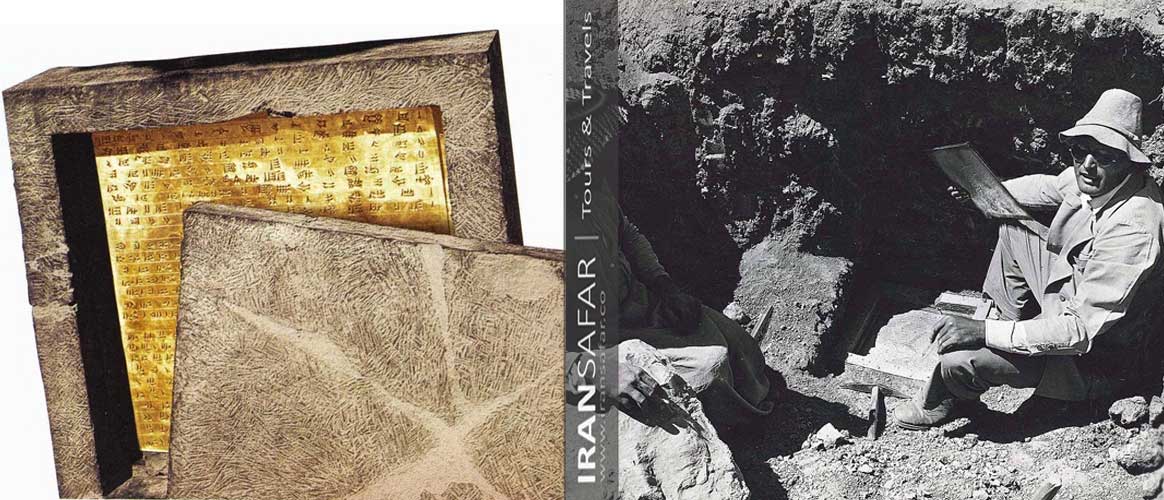

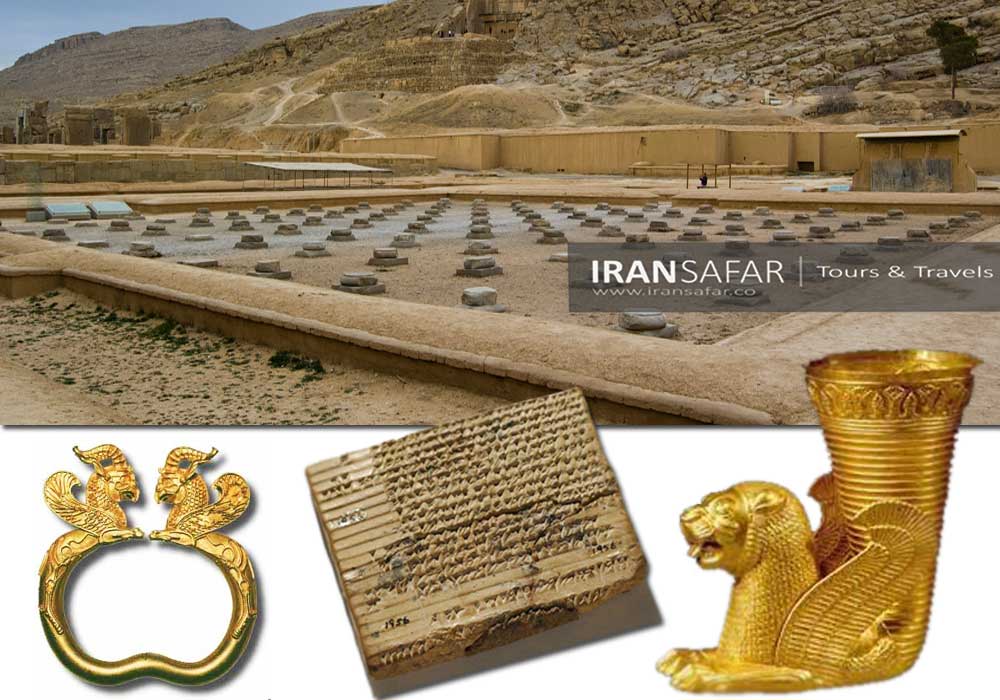

Apadana Hoard

The construction of this great and glorious palace was considered a lasting work, so Darius the Great ordered to name and describe Iranian Empire on four golden tablets and four silver inscriptions, in three languages in three languages of Ancient Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian. These inscriptions were put in four stone boxes, each 45 cm long and 15 cm high. They placed a golden inscription and a silver inscription with a few coins in each box and buried them in the four corners of the hall.

A pair of these cuneiform tablets are now displayed in the National Museum of Iran in Tehran. They contain trilingual inscriptions by Darius in Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian, which describes his Empire in broad geographical terms:

King Darius the great , king of kings, king of countries, son of Hystaspes, an Achaemenid. King Darius says: This is the kingdom which I hold, from the Sacae who are beyond Sogdia to Kush, and from Sind (Old Persian: “Hidauv”, locative of “Hiduš”) to Lydia (Old Persian: “Spardâ”) – [this is] what Ahuramazda, the greatest of gods, bestowed upon me. May Ahuramazda protect me and my royal house!

In 1933, a number of inscriptions, cut in stone, of Darius I, Xerxes, and Artaxerxes III were unearthed. They indicate to which monarch the various buildings are to be attributed. The oldest of these on the south retaining wall gives Darius’ famous prayer for his people: “God protect this country from foe, famine and falsehood.”

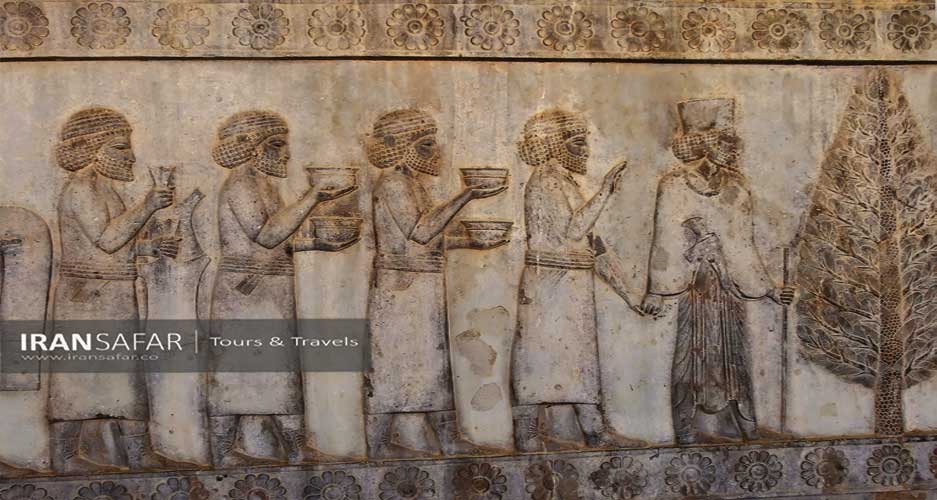

Apadana Eastern Stairway Reliefs

The king of the Achaemenid Persian empire is presumed to have received guests and tribute in this audience hall. Most impressive part of Persepolis, is the Apadana Stairway on the eastern wall, which can also be reached from the nearby Palace of 100 Columns . The engraved panels are adorned with rows of beautifully executed carvings depicting the annual processions of representatives of 23 subject nations of the Achaemenid Empire —perhaps on the occasion of the Persian New Year.

Three-tier panel at the eastern Apadana stairway is showing 23 delegations bringing their tributes to the Achaemenid court. This rich record of the nations of the times begins from Ethiopians in the bottom left corner, through a climbing pattern among other peoples, Aarabs, Thracians, Indians, Parthians and Cappadocians, up to the Elamites and Medians at the top right. The representatives of the twenty-three nations are shown bringing tribute while dressed in costumes suggestive of their land of origin.

Although the overall arrangement of scenes seems repetitive, an attempt has been made to portray all the delegates with their local clothes and weapons, as well as with the gifts they have brought. There are remarkable differences in the designs of costumes, headdresses, hair styles, beards and carried objects that give each delegation its own distinctive character and make its origin certain. Another means by which the design achieves diversity is by separating various groups or activities with stylized Cypress trees. Each delegation, consisting of three to nine members, is led by a Persian or Mede officer who takes the left hand of the head of the delegation in his hand and guides them to the court. Other members carry the gifts.

The Lydian delegation, identified by their distinctive hats. They carry a variety of objects, the first one holds two vases, the second two bowls, the third two metal armlets or wrist bands

Tripylon; The Hall of Council

In the center of the complex, there is a small but handsomely decorated hall that leads to other palaces through three gates and several corridors, and for this reason it is called “Central Palace” or “Trypilon” meaning a building with three gates. On its northern stairs, the Persian and Median nobles of the country have been depicted, who are shown hand-to-hand (in a friendly manner) going up the stairs to visit the Emperor. Because of these motifs and location of the palace, Trypilon is sometimes called the “council hall” and might have been used by the king to hold council with high ranking nobles. Of course, the exact function of Trypilon is still unknown but one of the more widely accepted theories is that the Achaemenid kings used this Palace to receive notables and courtiers in a private area, possibly to make important political decisions. Previously, the building of this palace was attributed to Darius the Great, but we have good evidence that its complete construction was done under Artaxerxes I.

Tachara Palace of Darius I

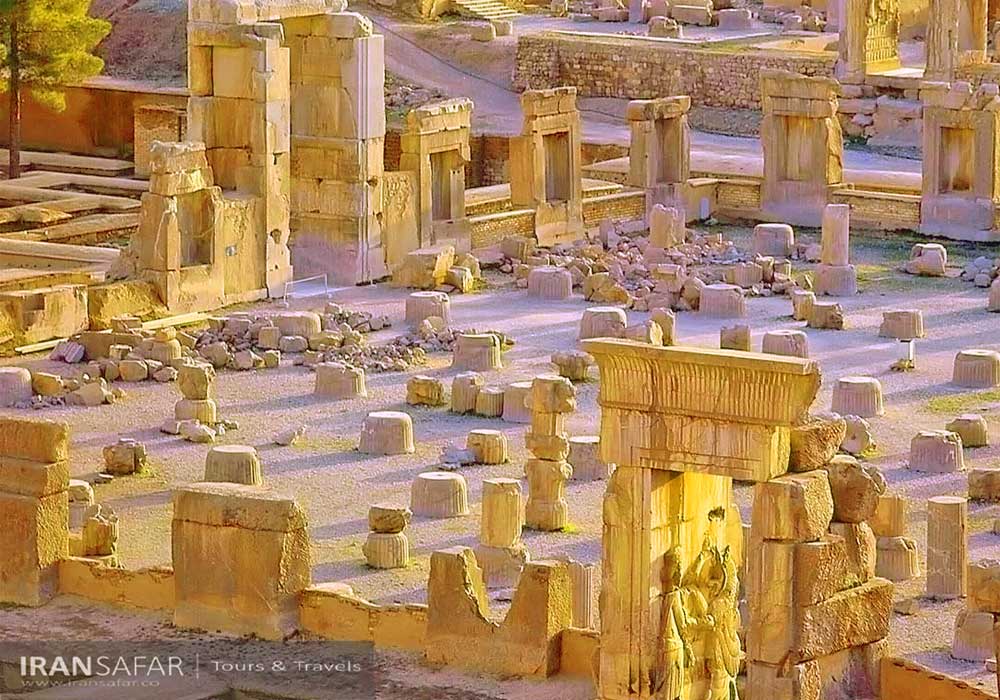

The South western corner of Persepolis is dominated by Palaces believed to have been constructed during the reigns of Darius I and his son Xerxes, The Tachara Palace or Darius’ private Palace is easily the most striking, with many of its decorated door jambs still standing and covered in bas-reliefs showing the king and his attendants. There is no sign of winding corridors in Tachara Palace and everything is built in a convenient size. This palace was originally built as the residence of Darius I and was used by some of his descendants. The walls of the palace were made of raw clay.

Tachara Palace is built on a platform that is 2.20 to 3 meters higher than the level of Apadana and its adjacent courtyard. Its design is rectangular and is facing south. It is 40 meters long and about 30 meters wide and consists of a 12-columned central hall with small side rooms, two square rooms in the north, each with four columns and with narrow and long side rooms. As the oldest of the palace structures in Persepolis, it was constructed of the finest quality gray lime stone. The surface was almost completely black and polished to a glossy brilliance. This surface treatment combined with the high quality stone is the reason for it being the most intact of all ruins at Persepolis today. Although its mud block walls have completely disintegrated, the enormous stone blocks of the door and window frames have survived.

Like many other parts of Persepolis, the Tachara has reliefs of tribute-bearing dignitaries. There are sculptured figures of lance-bearers carrying large rectangular wicker shields, attendants or servants with towel and perfume bottles, and a royal hero killing lions and monsters. There is also a bas-relief at the main doorway depicting Darius I wearing a crown used to be covered with gold leaves.

Persepolis Treasury

The treasury was built in the southeastern part of Persepolis during the reigns of Darius, Xerxes and Artaxerxes I. The palace consisted of 9 large and small halls consisting of several guard rooms and several large halls for the preservation of the royal treasury.

Numerous small palm-sized clay tablets have been unearthed from the “Treasury Administrative Archive Section” with Elamite inscriptions giving valuable information about workers and their wages. The reason for the miraculous good condition of these tablets was that these raw clay tablets were baked in the fire lit by Alexander and turned into baked clay. These tablets are clear evidence showing that slavery did not exist in Persian Empire and no one was forced to work in Persepolis and that all workers enjoyed insurance benefits and fair payment.

Palace of 100 columns

The second palace of Persepolis is a magnificent building in the east of Apadana, whose central hall had one hundred stone pillars (ten rows of 10 columns) and therefore it is called Palace of hundred columns or the “Throne Hall”. This area has an extravagant square hall measuring almost 7000 m2 and supported by 100 stone columns. The construction of this building was started by Xerxes and completed by Artaxerxes I and this is recorded in an inscription in the southeast corner of the hall. On both sides and one edge of this stone brick, an inscription is engraved in Babylonian cuneiform, the translation of which is as follows:

Construction of the palace probably began around 470 BC and was completed around 450 BC. In the beginning of Xerxes’ reign the Throne Hall was used mainly for receptions for representatives of all the subject nations of the empire. Later, when the Treasury proved to be too small, the Throne Hall also served as a storehouse and, above all, as a place to display more adequately objects, both tribute and booty, from the royal treasury. Concerning this, Schmidt wrote of the striking parallel in a modern example of a combined throne hall and palace museum where the Shah of Iran stores and exhibits the royal treasures in rooms and galleries adjoining his throne hall in the Gulistan Palace at Tehran.

Some scholars also believe that it was used to receive the military elite upon whom the empire’s security rested. an impressive array of broken columns remain and reliefs of the doorjambs at the southern side of the building show a king, soldiers and representatives of 28 subject nations.

Palace of 100 columns, Persepolis city, Iran

Palace of 100 columns, Persepolis city, Iran

Unfinished Gate

The Queen’s Palace

The Queen’s Palace, also known as Persepolis Harem, is located in the southern staircase of Hadish. It is called the Queen’s Palace or the King’s Harem due to its multiple private rooms and courtyards. According to a stone tablet found in the foundation it was built by Xerxes and is located at a lower height than other buildings. On the gates of this palace, most of which burned in the fire of Alexander the Great, are engraved effigies of the king entering the central hall with the eunuch’s crew, as well as the scene of the battle of the king with monsters. Today, this palace is used as Persepolis Museum and the central office of Persepolis facilities.

The main hall of this building has 12 columns and is connected to a large courtyard with a porch. On the doors of this hall, the image of Xerxes is engraved, but there is no trace of the installation of jewelry in them, because in this design, he was not in formal clothes. The layout and condition of the main hall, it can be concluded that this is where the Queen lived.

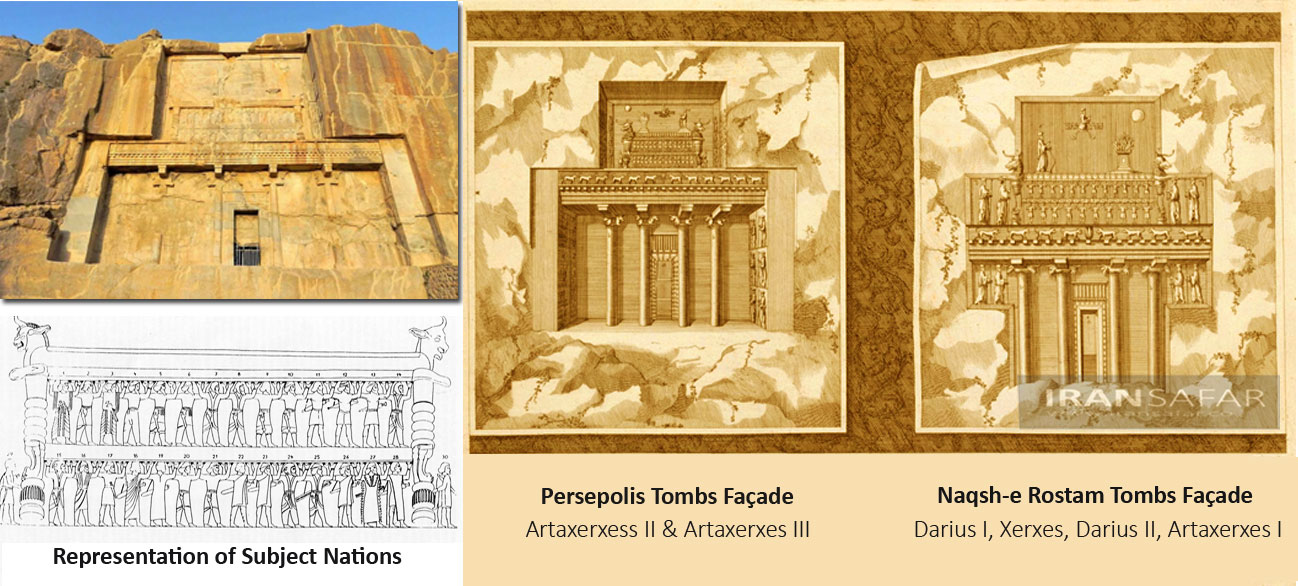

The Royal Tombs at Persepolis

In total, there are six rock tombs of the Achaemenid kings left, four of which are in Naqsh-e Rostam and two are located in Persepolis, at the foot of Rahmat Mountain and overlooking the site.

Achaemenid kings, Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III are buried at Persepolis city. These two tombs have been hewn out in the style of the tomb of Darius I in Naghsh-e Rostam and are similar because their builders have imitated the tomb of Darius the Great. Inside these tombs are several stone caskets, all of which have been broken and looted. According to the religious beliefs of the ancient Iranians, water, fire and soil were the three sacred elements created by “Ahura Mazda”, so it was not permissible to pollute them with filth. According to them, when the soul departs, the body cools down and the devil roots in the corpse; So they were not allowed to burn the dead or throw them in the water or bury them in the ground. One way was to put it in stone caskets and put the caskets inside the tombs dug in the cliffs, so that there would be no water, no fire and body does not touch the soil.

All Achaemenid tombs have the design of the imperial throne above, which is held by the representatives of the nations.

Persepolis Symbols & Motifs

The number of symbols used in ancient times, especially under the Achaemenids, may reach more than 50. These symbols can often be seen in Persepolis architecture and of course on excavated objects. But in the following, we will introduce some of these most popular and well-known symbols:

Lion-Bull Combat

One of the most beautiful and repeated relief carvings in Persepolis is the symbolic scene of lion and bull in combat. This relatively large and repetitive motif undoubtedly confirms a very important message of it. Roman Ghrishman, a famous American archaeologist who came to Iran during the first years of the Pahlavi dynasty, whose works are widely cited in Iranian archaeology, believes that this relief indicates the change of seasons, from cold winter to spring, marking the vernal equinox, in other words, Nowruz.

The Lion and bull is one of the oldest mythological symbols in the world. Many experts have already considered this symbol as the prominent sign of Mithraist art and have mentioned it as a sign inherited from Mithraic symbols. Actually the Lion is symbolizing sun and this contest refers to the passage of cold (winter-bull) and the victory of heat (sun-lion), the process of springing up and restoring nature with manifestation of Nowruz.

Cypress Tree

Various motifs of different flowers and plants, including cypress trees are repeated all over the site. Most of them are symbols of the greenness and reproduction of nature and spring. According to a Persian legend, it was the first tree to grow in Paradise. Because of the evergreen leaves and the wood was considered incorruptible, it became an image of immortality. For Zoroastrians, the cypress is a symbol of immortality as an evergreen tree that can seemingly live forever – the symbol of agelessness and longevity. The Persians regarded the cypress tree as a sacred plant.

Lotus

The lotus is a flower that is seen in most bas-reliefs of Persepolis city, particularly those related to the king’s effigies. The lotus, which is called Nilufar-e Aabi in Farsi, is regarded in many different cultures, especially in eastern religions, as a symbol of purity, enlightenment, self-regeneration and rebirth. This plant has a life cycle unlike any other; With its roots latched in mud, it submerges every night into river water and miraculously re-blooms the next morning, sparingly clean. In many cultures, this process associates the flower with rebirth and spiritual enlightenment. Because of these meanings, the lotus is often seen alongside divine figures in some cultures. For the Egyptians, the flower represents the universe. In Hindu culture, it is said that gods and goddesses sat on lotus thrones. And a longstanding Buddhist story states that the Buddha appeared atop a floating lotus, and his first footsteps on Earth left lotus blossoms.

In Iranian mythology, this flower is a symbol of the goddess Anahita, who occupies an important place in the rituals of ancient Persia. She is the goddess of water whose representation is a young woman. The lotus flower is considered to be the flower of Anahita. The ancient Zoroastrians may have considered this flower sacred because it grows in the middle of a swamp but unsuitable living environment can not be a reason for this being to grow poorly. The lotus motifs are almost everywhere in Persepolis as a symbol of peace and friendship. In the royal scenes of the site, kings have a royal scepter in one hand and a lotus flower in the other. The lotus flower can be considered as the predominant symbol of the Achaemenid Empire.

Faravahar

The Faravahar or Farr-e Kiyâni, is one of the most well-known symbols of Iranian religions such as Mazdaism and later Zoroastrianism practiced by majority of people living on Iranian plateau prior to the Muslim invasion of Persia in the 7th century AD. There are various ideas and interpretations of what the pattern symbolizes, and there is no concrete universal agreement on its meaning. However, it is commonly believed that the Faravahar serves as a Zoroastrian depiction of the Fravashi, or personal spirit. The Faravahar is one of the best-known pre-Islamic symbols of Iran and despite its traditionally religious nature, it has become a secular and cultural symbol, often representing a pan-Iranian nationalist identity. According to Persian scholars, Faravahar symbolizes the basic principles of the Zaroastrian religion: Good thoughts (pendār-e nik), Good words (goftār-e nik) and Good deeds (kerdār-e nik). Although, some Zoroastrians attribute the design to depiction of god Ahura Mazda.

Darius I, Founder of Persepolis City

Towards the end of the seventh century B.C., the Median kingdom as a powerful state, vanquished the Assyrians, and created a mighty kingdom in western Iran and northern Mesopotamia. In 550 B.C. they submitted to Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Iranian Empire, who was the son of a Persian prince and a Median princess, and hence, heir to the thrones of both Persia and Media. He built a capital in his homeland and named it Pasargadae, after the name of his own royal clan, the Pasargadae. The remains of this center lie 135km to the northeast of Shiraz. Having created an empire extending from the Mediterranean to the Oxus, Cyrus died (530 B.C.) fighting his nomadic neighbors, the Scythians of Central Asia. His brave son Cambyses added Egypt, Libya, and part of Ethiopia to the inherited empire. However, the men he had left at home in charge of his household and crown usurped his throne, and their leader named Gaumata, sat on the throne pretending that he was Bardiya (Also Called Smerdis) the younger son of Cyrus. Cambyses hurried home to face the impostor rival and his supporters, but died while still in Syria.

His cousin and one of his commanders in chief – or a member of the royal bodyguard – hastened to Media and with the help of six Persian nobles, he killed the impostor Gaumata. This story is still doubted by scholars and it would have been just made-up by Darius to justify the murder of real Bardiya, eligible successor of Cambyses.

In the Bīsitūn inscription of Kermanshah, Darius defended this deed and his own assumption of kingship on the grounds that the usurper was actually Gaumata, a Magian, who had impersonated Bardiya after Bardiya had been murdered secretly by Cambyses.

Darius organized the empire by dividing it into provinces (Satrapi) and placing Satraps to govern it. He was a clever politician and a farsighted state builder. He consolidated the system of empire by greatly improving upon its institutions, laws, communications, and economy. He constructed roads linking various important cities that eased trade, dug canals and constructed bridges, minted coins, and instituted the “Satrapy System” whereby each “province” of the empire was governed by three officials: a governor or “Satrap”, a military overseer, and a treasurer.

Darius also built a navy, explored the Indus valley, created a huge army and formed the Imperial Guard known as the “Immortals”, and levied fixed taxes and encouraged cultivation.

All of these greatly benefited his subjects and treasury. He further commissioned his secretaries to create a cuneiform script for his own‚ language (which he called “Aryan” meaning “Iranian” but we now call it the Old Persian) and employed it, along with Elamite and Babylonian cuneiform writings, in his royal proclamations. When the Athenians and other Greeks plundered his western territories and burnt the rich city of Sardis, Persia’s western provincial capital, Darius threatened them with a punitive expedition but did not live to carry out his threat.

His son and successor, Xerxes, was a man of magnanimity, artistic talent, and appreciation of beauty. He was forced by Darius’ generals to invade Greece but his armies and navy were defeated and he abandoned plans for further campaigns, instead, devoted his time to travels and building activities. Xerxes was followed by Artaxerxes I (466-24 B.C.), who continued the tradition of his father and built admirable palaces adorned with magnificent sculptures. He was followed by Darius II (424-04 B.C.), Artaxerxes II (404-358 B.C.), Artaxerxes III (358-38 B.C.), Arses (338-36 B.C.), and Darius III (336-30). Then Alexander of Macedon invaded Persia, and with him came the destruction of the Persian Empire and the disruption of the Iranian life and ascendancy. He destroyed a balanced and splendid foundation to build a shaky and unrealistic one, which when stripped of the excessive praises of Western historians, can be seen to have been feeble unoriginal. Alexander’s creation collapsed as soon as he himself collapsed under the effect of heavy drinking and megalomania.

Now, the Persian Empire founded by the Achaemenids and uprooted by Alexander was the greatest in history. It extended from the Danube to the Aral Sea and from the Indus Valley to Libya. Within this “world-empire” various nations lived prosperously and different cultures flourished. The

Persians based their administration upon magnanimity and liberalism but had a high regard for law and order. As long as the subject nations obeyed the central authority and paid a fair amount of taxation, they were free to follow their own laws and religious traditions, continue their artistic norms, retain their native languages, write in their own script, and maintain their traditional social system. In some cases, even local dynasties were left undisturbed and native kings retained their hereditary rights to kingship. Hence the Persian king was called “the Great King” or “the King of Kings”.

Due to their liberal policies on the one hand, and to their lack of experience in the field of monumental architecture the other hand, the Persians employed artists and artisans from among the subject nations, and paid them fairly generously to design and build palaces in various centers of the empire. In this way, different cultures and artistic styles were brought into contact resulting in a flow of mutual influences. From the intermingling of ideas and fashions, and under the supervision and planning of Persian masters, emerged the so-called Royal Style of art, which was both refreshing in its simplicity and delicacy and stunning in its unparalleled splendor and richness.

The Royal Style flourished under Cyrus the Great, Darius I, and his two successors; and although all subject nations contributed to its development, it must be mentioned here that the influence of the lonians has been exaggerated by many western scholars. It will be remembered that the Persians were but a handful of people in comparison to the vast number of their subject, and that they had to rule and guard a “world Empire” created in the space of only thirty years. This meant that they had neither enough manpower nor sufficient time to develop a distinctly “Persian” style in art. Consequently, it was natural that they should employ artists and artisans from among other nations. Thus, one may be justified in stating that the “Royal Achaemenid Art” was the seasoned art of the ancient Near East under new supervision, and that its crown jewel, Persepolis is the masterpiece of the artistic traditions of the ancient Near Eastern people. Indeed, it would be unfair to regard this monument solely as the heritage of the Persians. It is the heritage of Man …

Naqsh-e Rostam

About 8 miles (13 km) northeast of the main site, on the opposite side of the Pulvar River, rises a perpendicular wall of rock in which four tombs are cut at a considerable height from the bottom of the valley called Naqsh-e Rustam (Picture of Rostam), from the Sasanian carvings below the tombs once thought to represent the mythical hero Rostam.

It seems from the sculptures that the occupants of these seven tombs were Achaemenian kings; one of those at Naqsh-e Rustam is expressly declared in its inscriptions to be the tomb of Darius I, son of Hystaspes.

The three other tombs at Naqsh-e Rostam, besides that of Darius I, are probably those of Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I, and Darius II. The two completed graves behind Persepolis probably belong to Artaxerxes II and Artaxerxes III. The unfinished one might be that of Arses, who reigned at the longest two years, but is more likely that of Darius III, last of the Achaemenian line, who was overthrown by Alexander the Great.

Read more about Naqsh-e Rustam >>

Persepolis FAQ

Frequently asked questions about Persepolis:

A historical site that shouldn’t be missed while in Iran. It’s located in Marvdasht, near Shiraz, takes around one hour to get there. My friend and I visited Persepolis with a professional, intelligent and registered tourist guide that was arranged by Iran Safar Tours.

It is a marvelous visit … Thank you all!

Very useful information, thanks