Darius the great decided that the necropolis of the Achamenid king had to lie a few miles away from Persepolis, and he chose the cliff site of Naqsh-e Rostam (also Naqsh-i Rustam) where some old Elamite works already stood as the home of the large tombs hewn out of the vertical rock face. Instead of creating a mausoleum in the form of a house like that of C yrus the Great at the ancient site of Pasargadae, here the architectural formula was totally changed with the realization of colossal tombs cut directly out of the mountain face and visible from a great distance.

History of Naqsh-e Rostam

Naqsh-e Rostam is an ancient archaeological site with a rich history dating back over 3,500 years. There are works from the Elamite periods from 600 to 2000 BC, the Achaemenid period from 600 to 330 BC and the Sasanian period from 224 to 651 BC. which shows the strength of Iranian architecture before Islam. It is renowned for its remarkable rock-cut tombs and bas-reliefs. The site is situated approximately 12 kilometers northwest of Persepolis and served as a necropolis for the Achaemenid kings of Persia.

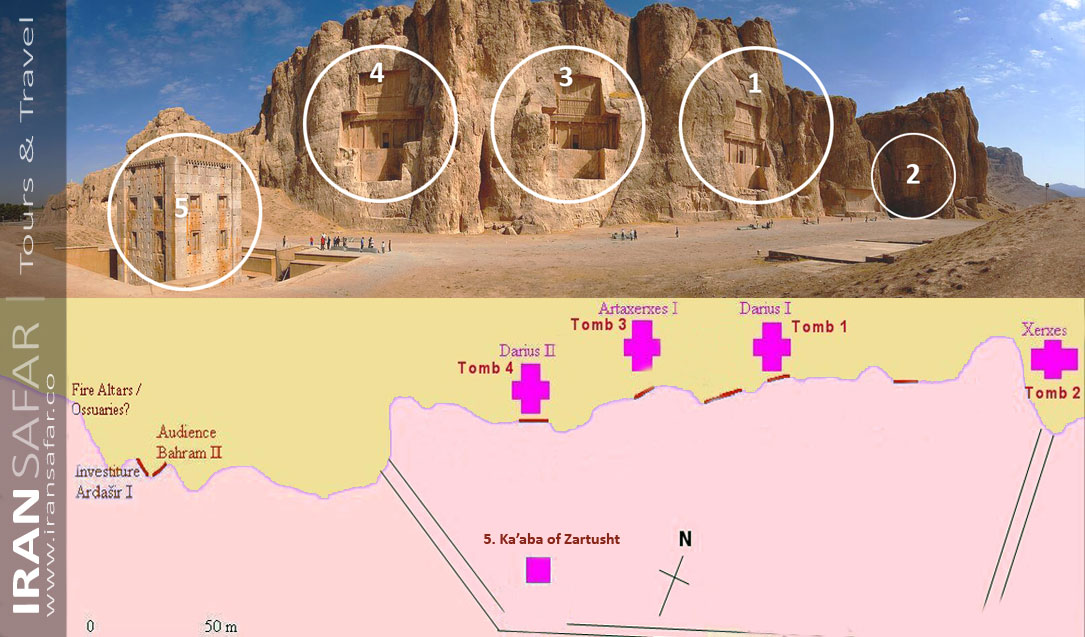

The rock-cut tombs, hewn into a cliff face, are believed to belong to Darius the Great and his successors, including Xerxes, Artaxerxes I and Darius II. These imposing tombs were created around 486-424 BC and are marked by ornate facades and inscriptions in Old Persian cuneiform.

Naqsh-e Rostam also features majestic bas-reliefs on top of the tombs that depict representatives of the nations under control of the Persian Empire from the Achaemenid period (circa 5th century BC). In these scenes, these figures are carrying a throne where the king is standing in front of a royal fire altar.

Over the centuries, the site remained significant during the Sassanid period (224-651 AD) when additional reliefs were added. Naqsh-e Rostam stands as a testament to the grandeur of ancient Persia and provides valuable insights into the culture, art, and burial practices of the Achaemenid and Sassanid empires. Today, it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a popular destination for tourists and history enthusiasts.

Also Read – Sassanid Archaeological landscape of Fars province

Naqsh-e Rostam Overview

At Naqsh-e Rostam there is a tall natural rock wall, a barrier that delimits the landscape for hundreds of feet. In this grandiose site, in re-establishing a link with the tradition of rock-cut tombs — such as the Median sepulcher at Kiz Kapan with its embedded columns and capitals with ‘Ionic’ volutes, imitating a palace and decorated with a bas-relief representing the Zoroastrian fire temples and rituals — the Achaemenid kings ordered the creation of amazing sculpted façades whose cross shape stands out in the recesses of the rock. There are three registers. The center is occupied by a transverse rectangular element that reproduces the façade of a palace: four embedded columns, whose capitals consist of double headed bulls, crown a single entrance way. The lintel of this latter is surmounted by an Egyptian Cyma, while the upper part is topped by a stone “rolling shutter” that is half lowered. Separated by denticulate frieze, the upper part has a large square bas-relief, the lower section of which has 28 bearers — the symbol of the nations under Persian dominion — lined up on two levels like atlases to support the king’s official litter. Above, the king, in an erect position, holds the emblematic arch and makes a ritual sacrifice in front of a fire altar below the image of Faravahar, which emerges in the middle of the sun disk supported by vulture or eagle wings. As regards the lower part, the base of the sculpted motif, the Persian sculptors who executed the hollow and smoothed the wall left it bare, like a silent beach, opposite the tomb.

Naqsh-e Rostam Site Plan

Click on the map to expand

Naqsh-e Rostam Achaemenian Tombs

The rock-hewn tombs are no less than 72.1 ft (22 m) in height and are situated well above ground level in order to prevent violation. In the interior, once past the door, which is set at a high level, without any other possible access except for removable ladders, visitors will note a straight inside corridor that runs parallel to the façade and leads to three chambers large enough to house several sarcophagus intended for the king and his family.

The first tomb of this kind, made for Darius the great (522-468 BC), is situated in the middle of the rock face. To the left, with the same shape and size, are the tombs of Xerxes (486-465 BC) and Artaxerxes I (465-424 BC), while to the right is the tomb of Darius II (423-404 BC)

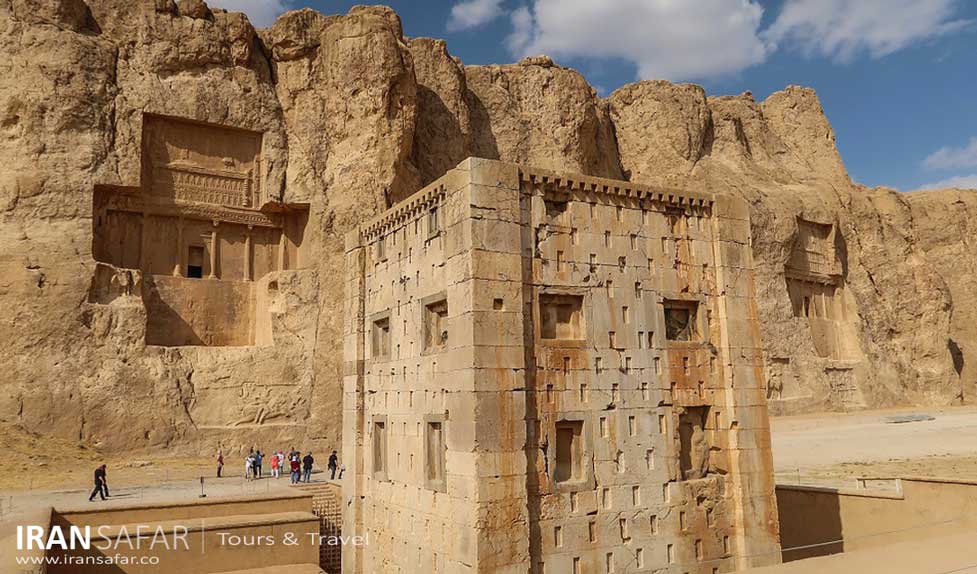

Kaaba of Zoroaster

At the left-hand end of the Naqsh-e Rostam cliff there is a square tower 22.9 ft (7 m) per side and 36 ft (11 m) high, which Muslims call Ka’aba-i Zartusht, or Ka’aba of Zoroaster. This construction has elegant limestone masonry that makes use of the subtle alternation of pits and hollows that lend rhythm to the walls, on which the false stone windows create strong contrasts.

The opinions of specialists concerning the function of this edifice, which is entered by a jutting stairway that leads to a door halfway up the structure, are not unanimous. Some consider it a fire altar, others a “library that housed the texts of the Avesta” (the sacred scripture of the Zoroastrians), and yet others a temporary tomb which holds the body until the proper tomb gets ready. It should be said that in Pasargadae an analogous edifice already existed, built with identical construction techniques but in this latter case the role of the structure is still wrapped in mystery.

To conclude this discussion of royal tombs, it must be pointed out that the last Achaemenian kings Artaxerxcs II (404-358 BC) and Artaxcrxcs III (358-338 BC) decided to build their tombs directly above the palaces of Persepolis, in the rock face of the mountain known as Kuh-i Rahmat, while the tomb of Darius III (335-330), who Alexander the Great defeated, was never finished.

Ka’aba of Zoroasteran, Naqsh-e Rostam, Shiraz, Iran

Ka’aba of Zoroasteran, Naqsh-e Rostam, Shiraz, Iran

Sasanian Bas-reliefs of Naqsh-e Rostam

The Sasaninans or Sassanid Empire who considered themselves to be worthy successors to the Achaemenids, revived the art of rock carvings to immortalize the most important events in their history.

Almost eight centuries later than Naqsh-e Rostam was founded, Sassanian monarchs Ardeshir I and his son Shapur I, commissioned rock panels consecrated to their glory; they revived the Achaemenid principle and had their works executed in prestigious localities. Thus, on the cliff face of Naqsh-e Rustam, at the foot of the grand Achaemenid tomb of Darius, Xerxes, Artazerxes I, and Darius II, Sasanians created Bas-reliefs showing their investiture or triumphal scenes.

Also Read – Sasanian Empire

1

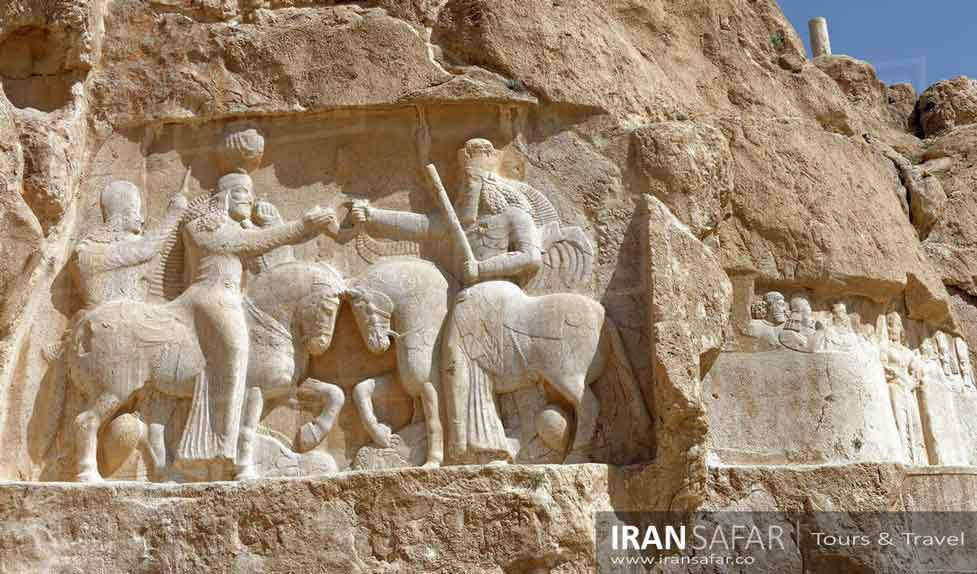

Investiture of Ardashir I

Ardeshir I who initiated the principle of the political continuity between the Achaemenids and Sasanians, had already glorified his victory over the Arsacid (Parthian) king Artabanus IV with huge rock-cut ‘Fresco’ at Firuz Abad that depicts an animated battle scene.

Again, on the bas-relief of Naqsh-e Rustam we find Ardeshir I, this time in an investiture scene on horseback. Ahoura Mazda (Zoroastrian God) also mounted and shown the same size as the king, is giving him the ring of power “Deihim” . The two figures on horseback are trampling the corpses of their respective enemies: on one side is Artabanus IV, the vanquished Parthian king, and on the other side is Ahriman, the spirit of Evil.

2

The scene of Valerian’s capture

Also to be found at Naqsh-e Rustam here Shapur I (241-272 AD) is also subduing the Roman emperor Philip the Arab, who is kneeling, while Valerian, who is standing, holds out his arms as a sign of surrender. These two major victories of the Sasanians epitomize the bitter war between the Persians and Roman-Byzantines, which lasted for several centuries.

The Roman–Persian Wars, also known as the Roman–Iranian Wars, were a series of battles between states of the Greco-Roman world and two powerful Iranian empires called the Parthian and the Sasanian. Conflicts between the Parthian Empire and the Roman Republic began in 54 BC; wars began under the late Republic, and continued through the Roman (later Byzantine) and Sasanian empires. Various vassal kingdoms and allied nomadic nations in the form of buffer states and proxies also played a role. The wars were ended by the Early Muslim Conquests, which led to the fall of the Sasanian Empire and huge territorial losses for the Byzantine Empire, shortly after the end of the last war between them.

Shapur I was the second Sassanid emperor to lead the Iranian army in battles with the Romans in successive wars with the Romans. According to historical evidences, he had three battles with the Romans, the third battle took place in 260 AD in Edessa (in current Turkey) with Valerian, the Byzantine Emperor. After the defeat of the Roman army by Shapur, the soldiers and commanders and Valerian himself were all captured and taken prisoner. Because of such a great victory, Shapur ordered that the scene of his victory be engraved in several places. Naqhsh-e Rostam is one of the places where the scene of Shapur’s victory in the battle of Edessa is shown in a prominent role.

3

The investiture scene of Narseh (c. 293-303)

In this relief, the king is shown as receiving the ring of royal power (Diadem) from a female figure that is supposed to be a divinity – Goddess of water Anahita.

However, the king is not shown in a way that would be expected at the presence of a divinity, and this led scholars to doubt the original theory and a new research suggested that the female figure can be a Queen, perhaps Queen Shapurdokhtak.

4

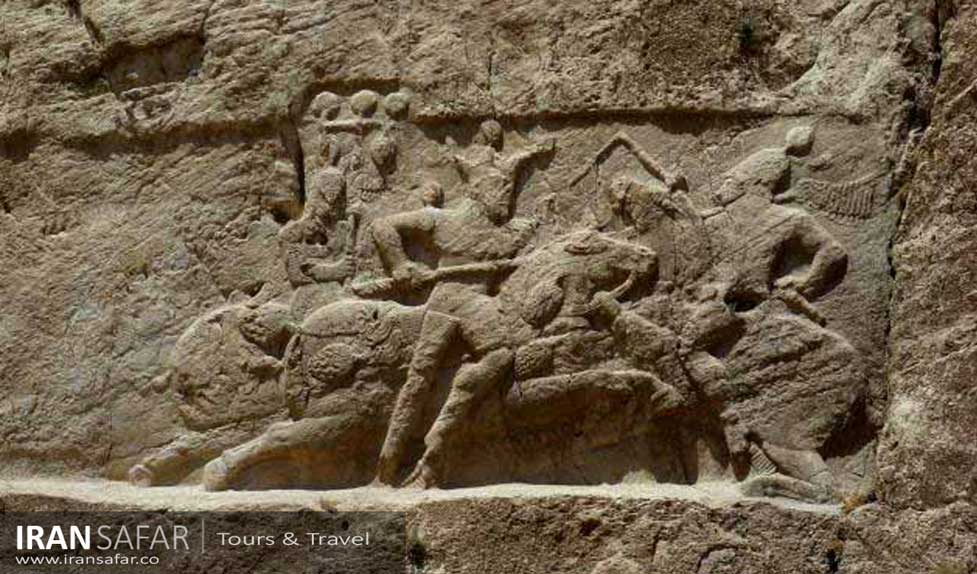

Battle Scene of Shapur II

Beneath the tomb of Darius II, a battle scene is carved, which is 7.60 meters long and about 3 meters wide. It shows a crowned figure on horseback planting a long spear into the neck of an enemy. The date of the role and identity of the victorious king is not known, but Henning and Schmidt consider it to belong to the time of Shapur II (309-379). Although the shape of the king’s crown has been bitten, its crenelations can still be recognized and its resemblance to Shahpour II’s crown is undeniable. The rider’s face is bitten, but his beard and ring are clearly visible.

5

Bahram II and courtiers

The relief of Bahram II and courtiers is a stone-carved monument from the Sassanid period. This painting is 5 meters long and 2.5 meters wide. Right in the middle of the carving, King Bahram II ( r. 271–274) with a huge crown ornamented with decorative wings, is standing, facing left. Three other people are depicted in a half-length form behind the emperor, all of them looking at him and bending the index finger of their right hand towards him as a sign of respect. In front of the king, five other people are depicted in half-length form, and they are also facing the king.

Originally there was an Elamite relief in this place which is considered the oldest ancient work in Naqsh-e Rostam. This work was carved on the cliff during the Elamite era. During the Sassanid era, Bahram II replaced the images of himself and his courtiers with the Elamite era motifs.

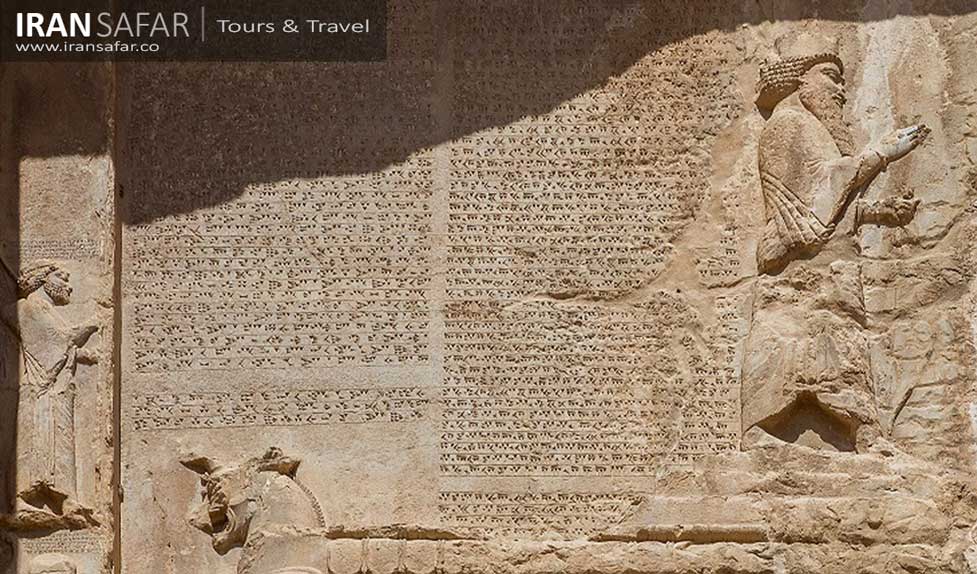

Naqsh-e Rostam inscription of Darius (DNA)

An inscription related to Darius the Great, referred to as the “DNa inscription” (Darius Naqsh-e Rostam inscription a) appears on the top corner of his rocky tomb. In this inscription Darius mentions his victories and his several great achievements of his lifetime. Its exact date is still unknown, but it is supposed to be from the last decade of his reign. Like several other inscriptions by Darius, the territories dominated by the Achaemenid Empire are clearly named and listed, in particular the areas of the Indus and Gandhara in India, referring to the Achaemenid occupation of the Indus Valley.

Lycian Tombs & Naqsh-e Rostam

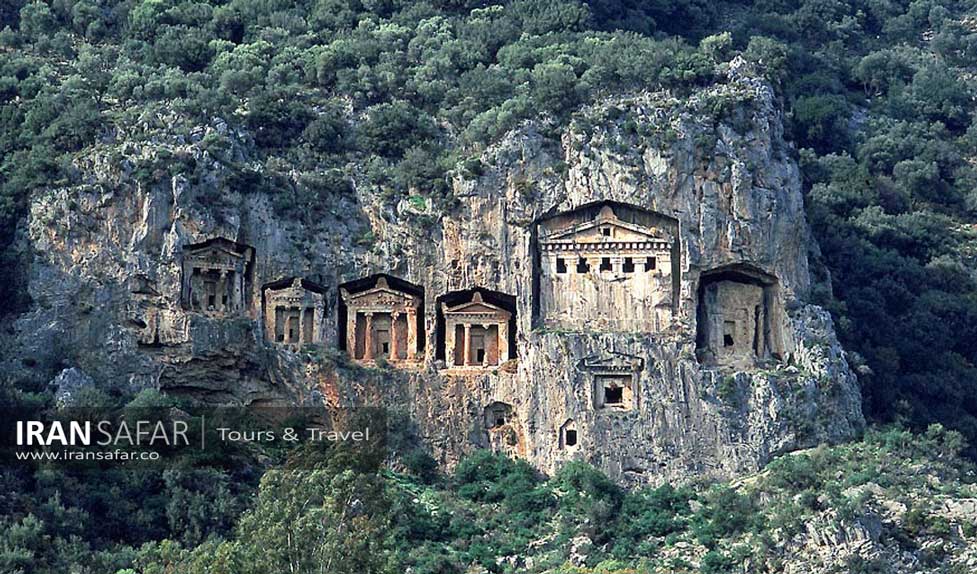

Possible links: The rock-cut tombs at the site of Kaunos, in Caria, Turkey are hewn out of the cliff that borders the estuary of the Calbis River. The sepulchers were built during the Achaemenid epoch after the destruction of the city, which took place in 546 BC, at the time of the Persian conquest.

It is no easy task to determine whether there is any relationship between the Persian rock-cut tombs of Naqsh-e Rostam and those in the provinces of Lycia and Caria, in southwest Anatolia. And should we be tempted to state there was such a relationship, would we be able to say how this influence came about? The territory of Lycia, situated among steep hills and rugged coastlines, was a wild country for a long period, hostile to Greek penetration. Like its neighbor Caria, it became part of the Persian Empire in the mid-6th century BC. Characterized by wooden residential areas, this region bears few traces of urbanization. Among these are some of the large rock-cut tombs in the cliff at Myra (Demre) or at Telmessos (Fethiye), for example, which date back to the beginning of the Persian epoch, especially the 5th century BC. However, the lack of precise data makes the archaeologists’ dating estimations rather vague in this regard.

Later on, around the 4th century BC, the forms of the sculpted façades in the rock face at Antiphellos or Kaunos, which were modeled after the Ionic Greek temple, introduced easily recognizable similarities. At Myra, a bas-relief carved in the live rock depicts a banquet scene: the servants are taking libations to the bier where the deceased lies. In a style that might be dated to the 4th Century, the reference to the banquet underscores the ubiquity of this motif.

These Lycian rock-cut tombs in the cliff of Telmessos were either modeled on the facades of the local wooden houses or imitated classical Greek temples.

The cliff that dominates the site of Myra (Demre) is literally perforated by tombs that look like 5th-century BC houses with a wooden framework. Could this rock art be related to the Persian tombs?

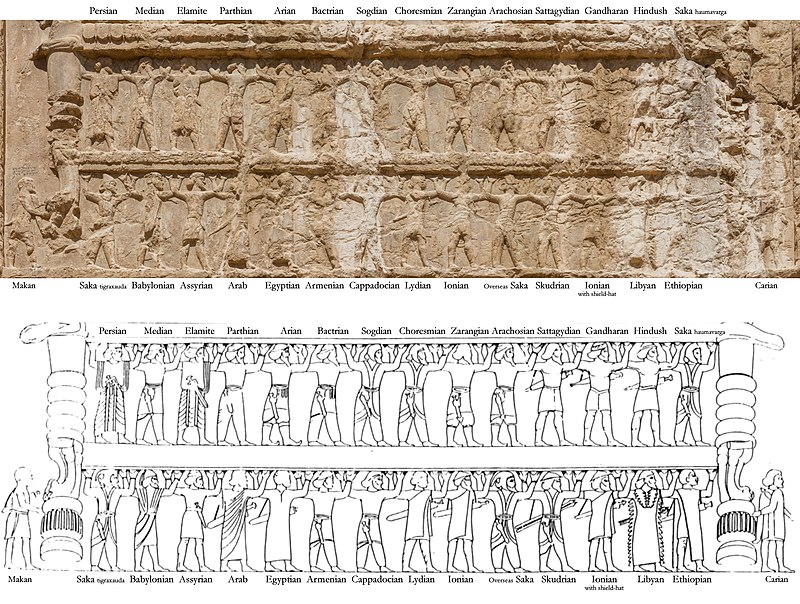

Representation of Nations at Naqsh-e Rostam

Representation of Nations at Naqsh-e Rostam

Nations under control of Achaemenids

The nationalities mentioned in the DNa inscription are also depicted on the upper registers of all the tombs at Naqsh-e Rustam, starting with the tomb of Darius I. The ethnicities on the tomb of Darius further have tri-lingual labels over them for identification, collectively known as the DNa inscription. One of the best preserved friezes is that of Xerxes I.

The nationalities of the Satrapies depicted on the top panels of the tombs and also mentioned in Darius inscription , from left to right: Makan, Persian, Median, Elamite, Parthian, Arian Bactrian, Sogdian, Choresmian, Zarangian, Arachosian, Sattagydian, Gandharan, Hindush (Indian), Saka (haumavarga), Saka(tigraxauda), Babylonian, Assyrian, Arab, Egyptian, Armenian, Cappadocian, Lydian, Ionian, Saka beyond the sea, Skudrian (Thracian), Macedonian, Libyan, Nubian, Carian.

Also Read – Lost Sassanid Soldier

Naqsh-e Rostam – FAQs

Q. What is the translation of the name “Naqsh-e Rostam”?

A. The name “Naqsh-e Rostam” translates to “Picture of Rostam.” Rostam is a legendary hero in Persian mythology, and the site is named after him due to a local belief that he was entombed here.

Q. What is the purpose of Naqsh-e Rostam?

A. The site consists of rock-cut tombs that were created during the Achaemenid Empire, a dynasty that ruled Persia from 550 BC to 330 BC. These tombs belong to several Achaemenid kings, including Darius the Great and Xerxes. The carvings on the tombs depict scenes from royal ceremonies and battles, offering a unique glimpse into the life and times of these ancient rulers.

Q. How can I get to Naqsh-e Rostam Archaeological Site?

A. Naqsh-e Rostam is easily accessible from Shiraz, a major city in Iran. You can reach the site by car or taxi, and it’s a short drive from Persepolis.

Q. What is the relief at Naqsh-e Rostam?

A. Actually there are several majestic rock reliefs here. One of the most striking features of Naqsh-e Rostam is the collection of Achaemenid and Sassanid bas-reliefs. These intricate carvings adorn the cliffs, showcasing kings in various royal and religious ceremonies. The most famous of these is the colossal rock relief of Shapur I, depicting the king on horseback, with his vanquished Byzantine enemies. The artistic detail and historical value of these reliefs are truly remarkable.

Q. Where is Xerxes buried?

A. Xerxes, the 4th Achaemenid king is buried in Naqsh-e Rostam site, likely in the easternmost rock-cut tomb.

Q. Are there any guided tours available at Naqsh-e Rostam?

A. Yes, guided tours are available at the site, but you need to book in advance. Please contact

Q. What is the best time to visit Naqsh-e Rostam?

A. The best time to visit Naqsh-e Rostam is during the spring and fall when the weather is pleasant, and the site’s surroundings are lush and beautiful.

Q. Is photography allowed at Naqsh-e Rostam?

A. Yes, photography is permitted at the site, so you can capture the breathtaking rock reliefs and ancient tombs.

Q. Are there any nearby attractions to visit along with Naqsh-e Rostam?

A. Yes, Persepolis, an ancient city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, is located nearby and is a must-visit when exploring the area. The Sassanian site of Naqsh-e Rajab is also one km away.

Ayda Khalili

Naghsh Rustam is like a time machine that takes you to ancient Persia. It’s an old place in Iran with huge rock tombs, beautiful carvings, and a lot of history. You can learn about the cool stuff that happened in Persia at Naqsh-e Rostam, where the past is super awesome and comes to life.

Farid Fatemi

Naqsh-e Rostam is also a significant site in Zoroastrianism, an ancient Iranian religion. The carvings and inscriptions found here are a testament to the deep-rooted religious beliefs of the time. The Ka’ba-ye Zartosht, a small structure at the site, is believed to have served as a Zoroastrian fire temple. Its design reflects the reverence for fire, a sacred element in Zoroastrianism.

Great Article! it is very interesting to visit these sites … I wish to travel to Shiraz to see Naqsh Rostam and Persepolis. Can you send me a guideline? I am from UK. Thanks