The Farsi term Taq-e Bostan, which means ‘arch of the garden’ is the name of one of those enchanting places so loved by the Persians in which nature and Man worked together to create a ‘paradise’. Laid out around a pool surrounded by large trees that provide refreshing shade, this site a few miles from Kermanshah is dominated by precipitous rock faces, at the base of which ancient sculptors expressed their artistry. Taq-e Bostan is the place where the sovereigns of Sasanian Empire (224-651 CE), in obedience to an ancient water cult dedicated to the goddess Anahita, built a series of extremely interesting rock-cut monuments.

History of Taq-e Bostan

Taq-e Bostan is a part of Biston mountain in the middle of Zagros mountains. It was built in the third century AD. At that time, the Sassanid kings were more inclined to build their inscriptions, memorials and bas-reliefs in Fars land, especially around Persepolis. But during the time of Ardeshir II, Taq-e Bostan was chosen for this construction of carvings, bas-reliefs and figures effigies.

The fame of Taq-e Bostan is due to the bas-reliefs made in the heart of the mountain. Since Taq-e Bostan is located in a fertile area with springs and green plains, it was mostly noticed by the Sassanid kings. Taq Bostan was also located on the Silk Road, and this was another reason why the Sassanid kings were interested in this area.

The three main parts of Taq-e Bostan

Here, however, instead of investiture or triumphal scenes carved on the rock, there are artificial grottoes entirely hewn out of the rock.

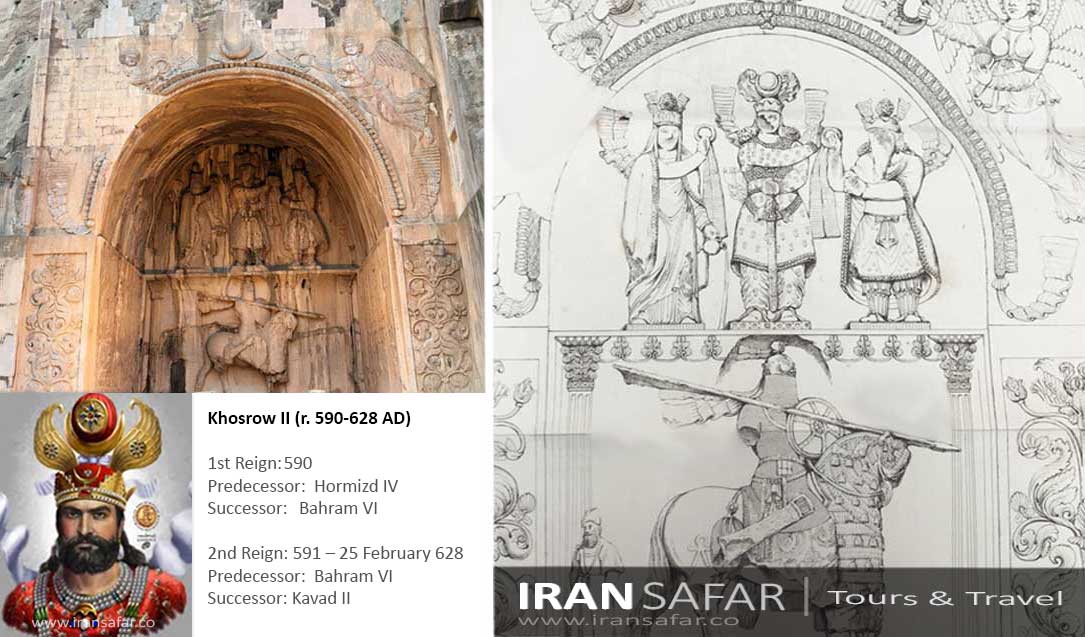

1. The large arch of the complex, which is also known as the large porch. It is related to the reign of Khosrow II also called Khosrow Parviz and in the years 590-628 AD.

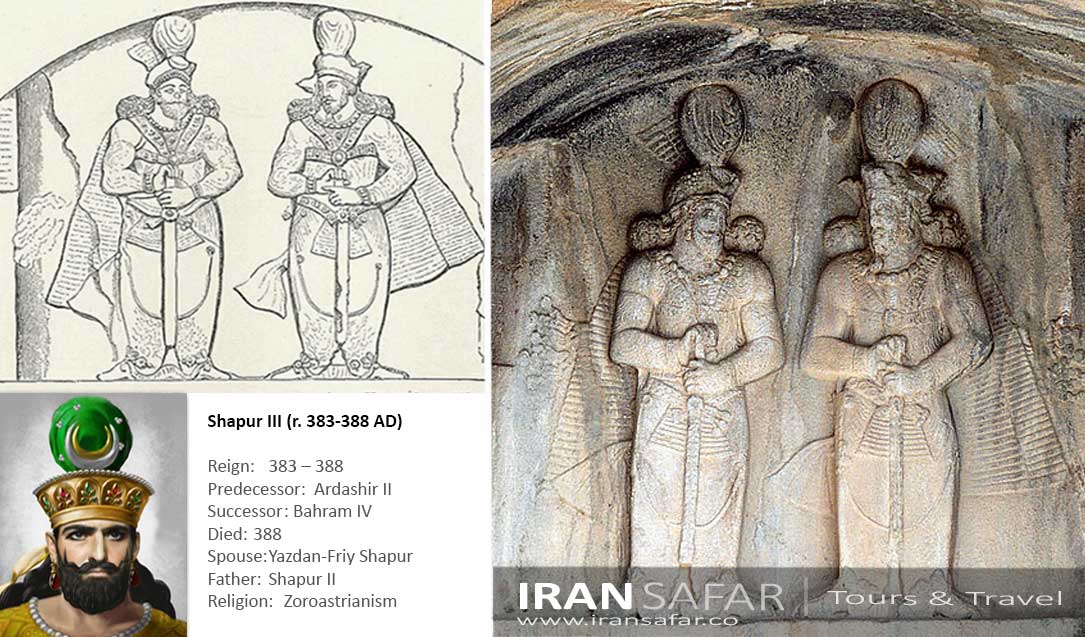

2. The small grotto of Taq-e Bostan, which is also known as the small porch, is the prominent image of Shapur III in 383-388 AD.

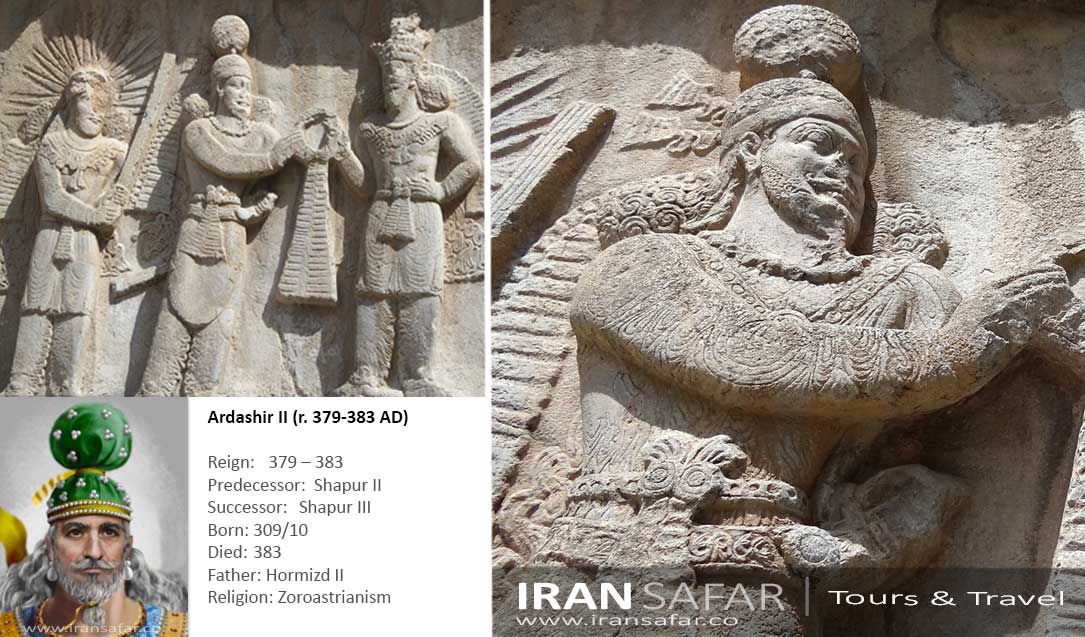

3. The relief or inscription of the coronation of Ardeshir II from the years 379-383 AD.

All the characters carved on the inscriptions of Taq Bostan collection are formed with such elegance and masterful precision that you can see all the details in them.

1

The Large Arch

The larger grotto — an interesting monument that must date to the reign of Piruz (457-484)- may have been finished by Khosrow II (590-628). This arch must have been the center of a Complex of three grottoes, the last of which (at left) was never hewn. It is most likely that this was due to the fall of the Sassanian Empire, which was overrun by Arab warriors.

The entrance of the large arch or to the first grotto at Taq-e Bostan (from the left) consists of a lovely arch that is the façade of the iwan: its elegant curve, which avoids the schematic rigidity of a simple round arch, has not only extremely refined decorative and floral motifs, but also ‘angels,’ that is to say, Roman-style winged victories wearing crowns. The images of Nike with marvelously carved wings are accompanied by these high-quality sculptures with grapevine festoon motifs in the ancient manner and by exotic plant motifs. Such a beginning immediately assumes an ethereal, albeit quite real, grace and charm: the female figures — the goddess Anahita and the Victories — make the Sassanian pantheon gentler.

At the end of the grotto visitors will see the apse, which consists of twos superposed registers. On the lower one is a ‘horseman’ on his steed, both larger than life-size and rendered in high relief that could almost be taken for sculpture in the round. The man, who is the king, is holding a lance and shield and wearing a helmet as well as a long coat of mail, while the horse is covered with a caparison. The equestrian statue heralds the motif of combat in the feudal world that flourished in the medieval Western world, but it is also a faithful image of the terrible “cataphracts” the ‘fully armored’ horsemen who struck fear into the Romans. In this case the sculpture represents King Piruz. On the upper level of the apse, on a sort of tympanum, Khosrow II stands between Anahita and AhuraMazda, who consigns him the ribboned crown.

Qajar Inscription

In the upper part of the wall on the left side of the great porch, a bas-relief from the Qajar period with an inscription in Nastaliq script is carved. In this scene, a Qajar governor and prince is sitting on a throne. His crown is a congressional crown and is similar to the crown of his father Fath Ali Shah. He is wearing a red pleated shirt. A belt is tied around the waist. A word and a dagger are hanging from his arms.

2

The Small Arch

Drawing inspiration from a creation commissioned by Shapur I in a natural cave at Bishapur, at Taq-e Bostan Shapur III (383-388) adopted the formula of an artificial cave.

Ardashir II’s successor, Shapur III, had the second grotto (from left to right) cut in the shape of an iwan, not far from the sculptures representing his investiture next to the effigy of his father Shapur II (309-379), thus legitimizing his assumption of power.

Shapur III was the Sasanian King of Iran from 383 to 388. He was the son of Shapur II (r. 309–379) and succeeded his uncle Ardashir II

During his five year reign, he settled the dispute over Armenia through diplomacy with most of it remaining under Sasanian control. To the east, he lost control of Kabul to the nomadic Alchon Huns. This was a significant loss, as the city had been a center of coin mintage since the 360s.

Shapur III was succeeded by his son Bahram IV.

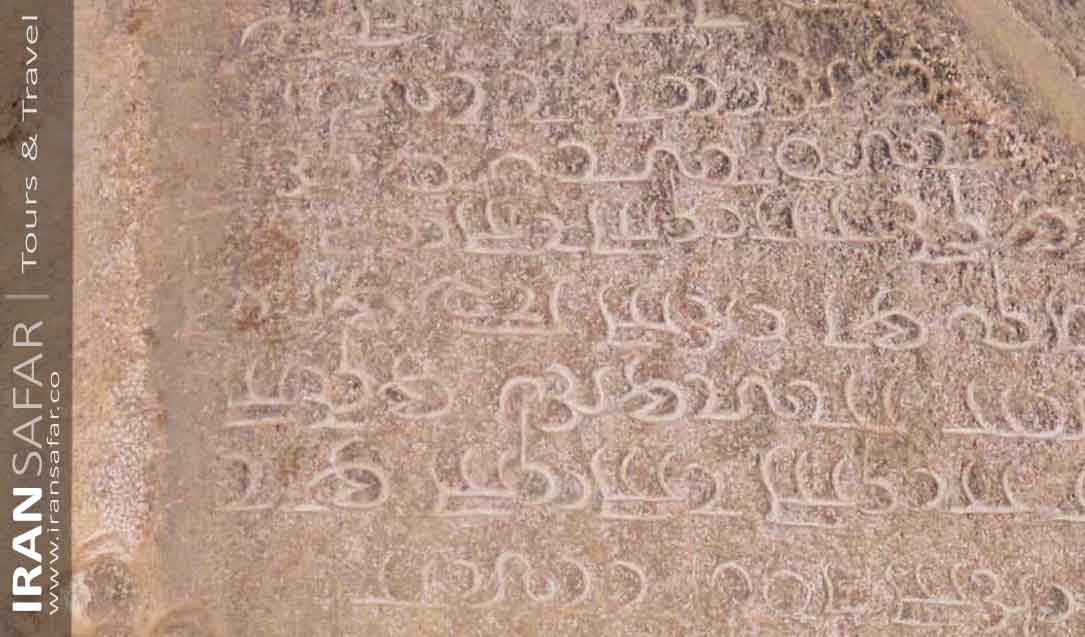

Inscriptions

Next to the two standing king of kings at the small arch of Taq-e Bostan, there are two inscriptions in Pahlavi script from the late forth century CE. They are almost identical and provide a generic information about the two kings who are first introduced as Magis of Ahura Mazda. Magis were priests in Zoroastrianism and the earlier religions of the western Iranians.

3

Investiture Scene of Ardashir II

Earlier than the construction of the arches, Ardashir II (379-383) had the first relief carving done at the site of Taq-e Bostan, depicting the king being crowned: while treading on a defeated Roman Soldier he receives a ribboned crown, the symbol of his authority, from gods, Mithra and Ahuramazda.

Ardashir II was the Sasanian King from 379 to 383 AD. He was the brother of his predecessor, Shapur II (r. 309–379), under whom he had served as vassal king of Adiabene, where he fought alongside his brother against the Romans. Ardashir II was appointed as his brother’s successor to rule interimly till the latter’s son Shapur III reached adulthood. Ardashir II’s short reign was largely uneventful, with the Sasanians unsuccessfully trying to maintain rule over Armenia.

Comment (0)