Ancient Persia, also known as the Persian Empire, holds a fascinating architectural heritage that continues to awe and inspire people to this day. The architectural features of ancient Persia showcase the brilliance of their builders and the richness of the culture of Iran. In this article we will talk about the various architectural features that were limited to the ancient Persia and explore their influences, construction techniques, and lasting legacy.

Features of Persian Architecture

Although the primary task as well as the greatest achievements of Persian architecture were in the service of religion, architectural activity was by no means confined to religious monuments and secular palaces. Other structures of considerable beauty and requiring equal skill and imagination were built throughout the land. The most important ones were bridges, bazaars, caravanserais, fortifications and gardens.

Persian Architectural Elements

In the realm of Persian architecture, the structure of a building comes to life through the combination of various spatial elements or “physical components.” Each component possesses its identity and significance within the overall design. These elements coexist gracefully without confusion or overlap. Each contributes to an ambiance that sets it apart, from the rest. Architectural Features in ancient Persia exemplifies a form of artistry guided by intelligent principles and techniques. It embraces grandeur, purity, spirituality, monotheism and other religious beliefs while paying attention to cultural values and traditions.

VAULT

Though of less spiritual importance, the vault is absolutely vital to the development of Persia’s great architectural achievements. From Sasanian Empire era or even late Parthian times, the vault in its various forms was without doubt the most important element in Persian structures. Its widespread adoption was necessitated by the lack of sufficient wood and timber to continue the Achaemenid habit of post and lintel construction. Vault construction was already in use from very early times. The Susa‘s Choga Zambil Zuggurat has entrance vaults dating from about 1200 B.C.

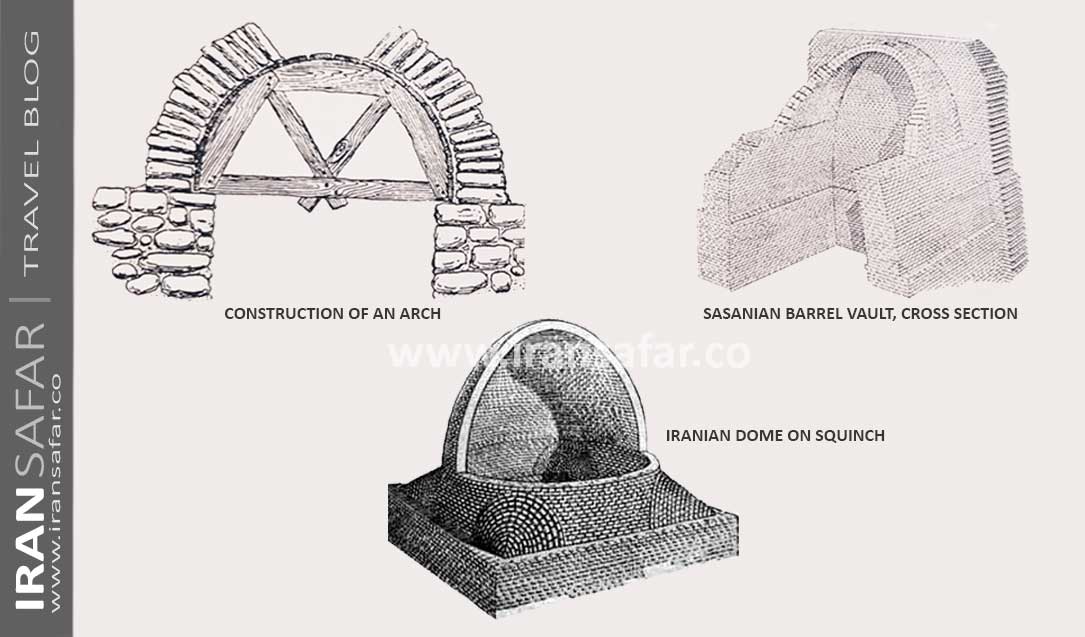

There are three kinds of vaults each originating from one element; the arch. If an arch is extended in depth it creates a barrel or tunnel vault. When two tunnel vaults intersect the resulting diagonal vaults are known as cloister or groined vaults. When the arch is rotated to form a vault, it technically becomes a dome.

This last, in a more complex form, can become a vault over a square plan and is capable of innumerable variations. The barrel vault or tunnel vault, the simplest of all, can be built relatively rapidly and cheaply. However, such a vault is restricted to a relatively narrow width. Also, since the weight and thrust of such a vault is carried by the walls, they cannot be pierced for windows without seriously – even fatally- weakening the structure; hence the vaults are dark. Despite this, many great Architectural Features in Ancient Persia were built in this form. The Single-Ivan structure, such as the reception hall of the Taq-i-Kasra (Ctesiphon Arch), is an example. Generally such vault are rather monotonous and structurally featureless, except when relieved by arched panels or recessed as at Firuzabad, Iran.

The problems presented by the barrel vault were in principle solved in Sasanian times by one of the most important inventions in the history of architecture, the transverse or reinforcing arch and vault: Supporting arches which run across the vault from side to side, thus dividing the bays.

The earliest example is the ruined Ivan-i-Kharkha in southwest Persia. These vaults are often very long, as in the best bazaars in Iran in Isfahan, Kashan and Shiraz where they extended for hundreds of feet.

DOME

The architectural element known as the “dome” is an iconic feature that has graced structures throughout history. A dome is an architectural element characterized by its hemispherical or semi-spherical shape, resembling an inverted bowl. It is typically placed atop a building, providing a roof or a covering that is both functional and aesthetically striking. The curvature of the dome allows it to distribute weight evenly, making it a stable and self-supporting structure without the need for additional internal supports.

The concept of the dome dates back thousands of years and can be traced to various ancient civilizations. One of the earliest examples of domes in architecture can be found in the ancient Near East, Mesopotamia and in Egypt. The ancient Egyptians used corbelled Arch to create dome-like structures in their temples.

In ancient Greece, the dome evolved into a more refined form, as seen in the with their beehive shape of domes. However, it was the Romans who significantly advanced the design and construction of domes. The most famous example is the Pantheon in Rome, built in 125 AD, featuring a massive concrete dome with an at its apex, allowing light to filter into the interior.

DOME Shapes & Forms

THE DOME presents many problems and took many forms in Persia. Sasanian domes were round, ovoid, or parabolic. Later they as- sumed still other shapes: low saucer-like domes that require es- pecially thick walls or buttresses to counter the excessive lateral thrust; or high domes set on tall cylindrical drums as in Timurid times; bulbous domes, expanding much or little beyond the cylin- drical base. The onion-shaped dome, a convention of some of the miniature painters, was not beloved by architects because of struc- tural problems involved and its feeling of restlessness, a fault particu- larly disliked by the Persians. Another type of dome used from the twelfth century was adopted to crown circular or octagonal Ires such as tomb towers with a tent or polyhedral roof.

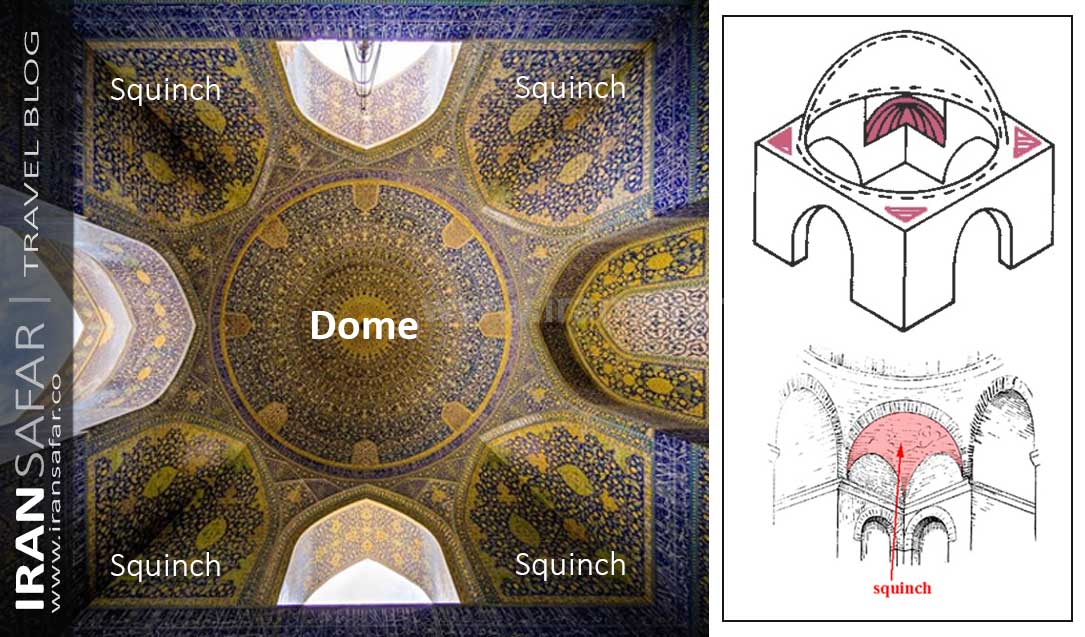

With regard to the Dome placed over a square plan, the principal problem is how to manage the transition from square below, to circle above. For centuries this problem baffled the very competent Roman engineers, who did not provide an attractive or even assured solution. The earliest solution was reached by Persian engineers and masons. They realized that the answer required the development of a third section, a zone of transition between the square chamber below and the round dome above. They innovated an element called Squinch which involved creating an arch across each corner thereby reducing the square to an octagon with a further ring of small arched panels to reduce the eight sides to sixteen, which is close to being a circle.

SQUINCH

The history of the Squinch is essential to the history of the Persian architecture. In dome structures in Iran, an architectural element called Se-Konj , – in English “Squinch” – is used. A squinch is a structural device that provides a smooth transition between a square or polygonal base of a dome and the circular drum on which the dome rests. It is commonly used to support the base of a dome when the dome’s shape is different from the shape of the supporting structure.

The squinch serves as a type of transition zone, allowing the dome to sit securely on the walls while maintaining its circular form. It effectively converts the square or polygonal space into an octagonal or circular base, providing a stable foundation for the dome.

Dome on squinch, an architectural feature of ancient Persia

Dome on squinch, an architectural feature of ancient Persia

In Iranian architecture, particularly in the construction of Islamic buildings such as mosques, the use of squinches has been a prevalent technique for centuries. They are basically of two types: the hollow round-backed squinch of Sasanian period, and later a simple groined squinch. The problem that immediately followed the initial use of the squinch was how to fill its hollow space. The infinite number of ways in which the squinch is filled, divided or multiplied are astonishing in their variety.

IVAN

In Persian architecture, “Ivan” or “Iwan” refers to a specific architectural feature that can be commonly found in traditional Persian and Islamic buildings. In the outer part of old Iranian buildings, there is an open, vaulted space with walls on three sides and an open entrance on one side. The use of this element goes back to the Parthian period, and it has taken various forms throughout history. Ivans are not only architecturally significant but also serve functional purposes. They provide shade and shelter from the elements, making them popular gathering places for familial, social or religious activities. These porches are surrounded by the building on three sides and open to the yard on the other side. Ivans can be seen in various types of Persian architectural structures, including mansions, mosques, palaces, madrasas (religious educational institutions), and other historical buildings.

Architectural Heritage of Ancient Persia

Iranian architecture has more than 6000 years of continuous history, which dates back to the 4th millennium BC. Since then, this art has continuously developed and evolved in relation to various issues, especially religious causes. Iranian architecture is known as one of the most famous architectural styles in the world, which has a special value compared to other countries in the world. The glory of Iranian architecture, which displays the art of Iranian architects and elements of Iranian architecture, is due to features such as proper design, accurate calculations, the correct form of covering, and compliance with technical and scientific issues in Iranian buildings.

Bridges of Iran

There are many bridges in Iran. Some of these bridges have a high architectural value and are considered engineering masterpieces.

In the southwest Iran, BRIDGES often combined with dams for much needed irrigation, were essential. Bold designing and first-class constructional techniques were indispensable; from Sasanian times they were highly developed. Roman prisoners, including masons captured at Shapur‘s defeat of Byzantine Emperor, Valerian, made important contributions: they laid out the mile-long bridge and dam at Shushtar. The remains of the great Pul-e Dukhtar near Sarvistan, 70 feet high and originally of huge span, confirm the contemporary description of even more sensational structures.

These bridges were more than means for crossing a river: they were often of notable beauty in proportions and contour. The later bridges were increasingly elaborate and were sometimes combined with mosques and caravanserais. Thus, two complex bridges over the Zayandeh Rud river at Isfahan, the Si-o-Se pol bridge (or Allahvardi Khan bridge), built by that favorite general of Safavid Empire, and the Khadju bridge built by Shah Abbas II, serve both as bridge and dam. Planned also for enjoyment, they are places for tarrying as much as transit.

Also Read : Zayandeh Rud River

Persian Gardens

Persian gardens were celebrated for their symmetrical layout and advanced water management systems. The concept of paradise gardens was central to their design, combining natural beauty with engineered water channels and fountains. The concept of Persian gardens has left a lasting legacy in landscape design, emphasizing harmony with nature and the use of water as a central feature.

Read More : Persian Garden

Caravanserais

CARAVANSERAIS of Iran were quite as indispensable as bridges to the maintenance of commercial and economic prosperity. Among early examples of caravanserais are the great caravanserai built by Harun-al-Rashid about 889 on the road to Tus and the 10th century caravanserai built by Adud ad-Dawla. In the midst of a formidable desert, between Samarkand and Bokhara, Sultan Sanjar sometime before 1078 built an immense caravanserai, the magnificent Rabat-i-Malek. At one time in the 17th century the caravanserais along the major roads -such as the Silk Road – were reputed to be only 20 miles apart, sometimes even closer. They were often quite large and intricate in plan and a famous Seljuk caravanserai at Zabzavar contained 1,700 chambers. These caravanserais constitute one of the triumphs of the Persian architecture. Nowhere can we find a more complete accord of function and structure. The basic plan for later caravanserais is constant from structure to structure. All are essentially concentric, with the outer wall quite blank, allowing access only through a single and easily defended portal. The central court is surrounded by open arcades, like a mosque or madrassa.

Read More : Famous Caravanserais of Iran

Badgir: a windcatcher

Undoubtedly, the “Badgir“s of Iranian desert towns are of the most sophisticated and amazing Architectural Features in Ancient Persia. Also known as a “Wind Tower” or “Windcatcher,” they are traditional architectural elements that have been used for centuries to provide natural ventilation and cooling to buildings in hot and arid climates.

Wind towers were mostly used in the central and southern parts of Iran. Their main function has been to ventilate the climate in the house, and they were usually built in the form of towers on top of roofs or water reservoirs. Badgir consists of a tall, chimney-like tower with openings on the top and sides, strategically positioned to catch prevailing winds and direct them downwards into the interior spaces of the building.

Here’s how a Badgir works:

Wind Capture: The Badgir is designed to capture even the slightest breeze from any direction. The tower’s openings on the sides are oriented towards the prevailing wind direction, ensuring that the air is channeled into the tower.

Downward Airflow: As the wind enters the Badgir, it moves downward due to the pressure difference caused by the height of the tower and the openings at the top. This descending air creates a gentle breeze inside the building.

Cooling Effect: There is usually a water pond at the bottom of the wind tower. As the wind passes through the shaft, it reaches the water, cools down and moves into the interior spaces of the building.

Ventilation: The wind is directed into the building’s interior through a system of ducts and vents. These ducts distribute the air to different rooms, providing ventilation and cooling throughout the structure.

Iranian Ice House

Indeed, the Iranian old Ice Houses, known as the yakhchāls, are fascinating examples of ancient ingenuity in preserving ice in regions with hot climates. These adobe structures were designed to leverage natural environmental conditions for the creation and storage of ice.

The ice-making pool served as a key component in the process. During the winter, water would freeze in the pool, creating a supply of ice. The high shade wall and fence were strategically designed to cast a shadow over the pool during winter days, preventing direct sunlight exposure and aiding in the ice formation process. This shaded environment helped maintain lower temperatures and protected the ice from melting. The deep tank covered by a conical dome, often constructed with materials like mud and clay, provided insulation to keep the ice cool.

These ancient ice houses stand as tangible reminders of the resourcefulness of past civilizations in adapting to their environments and making the most of available natural resources for practical purposes like preserving ice in the absence of modern refrigeration technology. One of the best examples of an Iranian Ice house is found in the town of Meybod.

Read More : Iranian Ice House

Iranian Pigeon Towers

The construction of large pigeon towers, especially during the 15th and 16th centuries under the Safavid Empire in Iran, was not just a fancy architectural choice but served practical and agricultural purposes. These structures played a crucial role in supporting agriculture and were more than simple pigeon nests. Several factors contribute to the understanding of their significance:

Fertilizer Production

These towers were specifically designed for pigeons, recognizing their significance not for their meat but for their valuable excrement, a potent fertilizer used in melon fields. The primary purpose of these large pigeon towers was to harvest pigeon droppings, known as guano. Pigeon droppings are rich in nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, essential nutrients for plant growth. By collecting the droppings in significant quantities, farmers could use them as highly effective natural fertilizers for their crops.

Gunpowder production

Additionally, the pigeon’s guano that was collected from pigeon towers of Iran played a role in gunpowder production. Guano, which is a type of bird droppings, was historically used as a source of nitrogen for the production of gunpowder.

Leather industry

Indeed, pigeon guano has been historically used in various industries, including leather tanning. Tanning is a process that converts animal hides into leather, making it more durable, flexible, and resistant to decay. During traditional tanning methods, hides are soaked in a tanning solution. The ammonia in pigeon guano acts as a natural source of alkalinity in the tanning solution. This alkalinity helps to break down collagen fibers in the animal hides, making them more pliable and flexible.

Read More: Pigeon Towers of Iran

Comment (0)