Persian art or Iranian art has one of the richest art heritages in world history and has been strong in many media including architecture, painting, weaving, pottery, calligraphy, metalworking and sculpture. At different times, influences from the art of neighbouring civilizations have been very important, and latterly Persian art gave and received major influences as part of the wider styles of Islamic art. This article covers the art of Persia up to 1925, and the end of the Qajar dynasty; for later art see Iranian modern and contemporary art, and for traditional crafts see arts of Iran. Rock art in Iran is its most ancient surviving art. Iranian architecture is covered at that article.

Bakhtiary nomads weaving carpet

Bakhtiary nomads weaving carpet

From the Achaemenid Empire of 550 BC–330 BC for most of the time a large Iranian-speaking state has ruled over areas similar to the modern boundaries of Iran, and often much wider areas, sometimes called Greater Iran, where a process of cultural Persianization left enduring results even when rulership separated. The courts of successive dynasties have generally led the style of Persian art, and court-sponsored art has left many of the most impressive survivals.

In ancient times the surviving monuments of Persian art are notable for a tradition concentrating on the human figure (mostly male, and often royal) and animals. Persian art continued to place larger emphasis on figures than Islamic art from other areas, though for religious reasons now generally avoiding large examples, especially in sculpture. The general Islamic style of dense decoration, geometrically laid out, developed in Persia into a supremely elegant and harmonious style combining motifs derived from plants with Chinese motifs such as the cloud-band, and often animals that are represented at a much smaller scale than the plant elements surrounding them. Under the Safavid dynasty in the 16th century this style was used across a wide variety of media, and diffused from the court artists of the shah, most being mainly painters.

Persian Carpet

Persian art is best known in the West for its carpets. Europeans had their first encounter with Persian rugs by at least the 15th century and the initial impression has never changed; in carpet weaving Iran is considered to have no equal. No researcher can define the exact beginning date of carpet weaving in Iran. The earliest-known Iranian carpet, now named Pazyrik after the archaeological site in Siberia where it was exhumed from the frozen tombs of Scythian chiefs, dates from about 500 B.C.

a carpet gallery in Isfahan, Iran

a carpet gallery in Isfahan, Iran

The value of Iranian carpets is determined to a large extent by their patterns. Before weaving a carpet, a professional weaver usually designs the patterns and makes a paper model, representing one quarter of the carpets surface; nomads usually improvise while weaving. The carpet consists of the main portion and the margins; the margins, in turn may be divided into three sections. There is an astonishing variety of patterns in Iranian carpets. Their elaborate composition and minute details reflect a poetic vision of the world and a belief in the efficacy of symbols. Of all the themes which occupy the mind of a Persian carpet designer, the garden is particularly important. Some historians report that when the Muslim Arabs conquered Persian capital “Ctesiphon” in 637, among the fabulous booty they carried away was a huge carpet, depicted a formal Persian garden, made for audience hall of the king’s palace; the idea of Paradise.

Main present carpet weaving centers in Iran include: Qom, Isfahan, Tabriz, Kerman, Nain, Yazd, Kashan and nomadic regions like Baktiari and Qashqai.

Wool quality

One of the most important factors in the longevity and beauty of a rug is the quality of the wool. We have found that the best carpet wools in the world come from Iran, which is why Iranian rugs have always been the most sought after rugs in the world.

Wool quality is determined by the breed and diets of the sheep from which the wool is shorn. Minerals in their water can give the wool extra strength and luster. Feel the rug, massaging the wool between your fingers. If it feels strong, supple, and rich, as opposed to dry, harsh, and crisp, then the wool is of good quality. One thing to be particularly careful of is “tabatchi” or dead wool. This is wool shorn from sheep that have already been slaughtered. Tabatchi wool is

very brittle, and will wear out in a very short time. Rub your hand firmly over a spot on the surface of the carpet a few times. If you have more than a tiny bit of loose wool fiber, it is a likely that the rug is made of tabatchi wool. These rugs should be avoided if possible, as they will wear to nearly nothing and the rug will lose all its value within a span of just a few years.

The best wool is called “kurk”. Kurk comes from the first shearing of lambs between 9 and 14 months old, and only from the neck and under the arms. Kurk has a feel almost like velvet, but is exceptionally strong.

Knot count

While it’s true that a higher knot count means that the carpet took longer to make, there are other factors to consider. Knot counts in rugs can vary from as low as 40 per square inch to as high as 1200. Think of knots as pixels on a screen. The finer the knot count, the higher the resolution of the picture. Therefore, higher knot counts work best for rugs with a great amount of detail. Curvilinear designs need higher knot counts. Geometric designs can often do with far lower counts and still be very high quality pieces.

In Iran, most knot counts are measured in “radj”. One radj is the number of warp threads in 7 centimeters. A 30 raj carpet is usually considered “commercial” grade, with somewhere between 120 and 140 knots per square inch. Carpets of 50 radj and higher are considered fine carpets. A 50 radj carpet usually has about 330 knots per square inch. An 80 raj carpet, has about 900 knots per inch, and is a truly exceptional piece.weavers normally can tie 4,000 up to 8,000 knots a day. This means that a 9′ X 12′ carpet woven at 350 knots per inch can take over two years for one single weaver to make.

Enamel | Mina kari

Enamel or Minakari, “This dazzling art of earth and fire…saturated but lucent colours”thrives today in Isfahan. When minakari artists say they do not know when their art began here, they mean they are not sure when in the Safavid period – yet enamel onterracotta was known at Susa 1500 B.C., on metal was fully developed in the Oxus treasureof the sixth to fourth centuries B.C and after 500 B.C . “it was probably more elaborated inPersian than anywhere else.” Minakari today refers only to that enamel painted flat on aMetal base, usually copper, and covering it completely. It does not include champlevé norCloisonné , enamel contained within gouged out cavities or wired borders, nor grisaille, theMonochrome sculptured relief enamel. Chardin wrote that enamel was one of the arts the Isfahanis did not know how to do, yet a piece remaining from that time is described today as “one of the finest extant examples of Persian enamel, with a pattern of birds and animals against a floriate ground, rendered in light blue and green opaque enamels and dark blue, Green, yellow and red translucent enamels.”

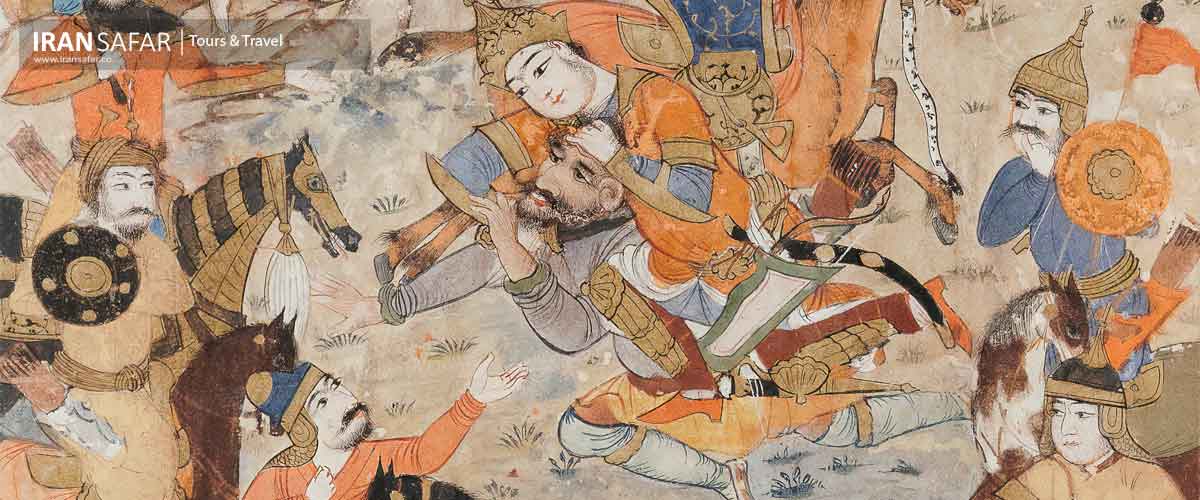

Persian Miniature Painting

A Persian miniature is a small painting on a tiny piece of camel bone, paper, a book illustration or a separate work of art intended to be kept in an album of such works called a murraqa. The techniques are broadly comparable to the Western and Byzantine traditions of miniatures in illuminated manuscripts. Although there is an equally well-established Persian tradition of wall-painting, the survival rate and state of preservation of miniatures is better, and miniatures are much the best-known form of Persian painting in the West, and many of the most important examples are in Western, or Turkish, museums. Miniature painting became a significant Persian genre in the 13th century, receiving Chinese influence after the Mongol conquests (1219), and the highest point in the tradition was reached in the 15th and 16th centuries. The tradition continued, under some Western influence, after this, and has many modern exponents. The Persian miniature was the dominant influence on other Islamic miniature traditions, principally the Ottoman miniature in Turkey, and the Mughal miniature in the Indian sub-continent.

Ghalamkar | Painting on Textile

Ghalamkar is a type of Textile printing by using patterned wooden stamps. The stamps are mostly made of pear wood which has which has a good flexibility and density for carving and lasts longer. In each Ghalamkar workshop, there are hundreds of different patterns consisting of arabesque designs, flora and fauna designs, geometric designs, pre-Islamic designs, hunting scenes, polo games and Persian poems. Esfahan is one of the most important producers of this type of art throughout the world.

Blue, red, black, green, and yellow are the main colors of Ghalamkar used in this handicraft. Traditionally, dried pomegranate peel, saffron, turmeric, black alum, dried herbs, and indigo used to dye the fabrics naturally. But today chemical colors and inks are used as well.

After finishing printing, the fabric is first steamed for at least an hour to stabilize their designs. Then, it is taken to the riverbed and kept in some basins to be soaked well. Afterwards, the pieces should be boiled with a special color stabilizer, then they are washed again in the river as the final step.

Comment (0)